“I’m a made in America artist,” says artist Michiko Itatani when asked how being from Japan influences her work. Itatani, who was born in Japan in 1948, moved to Chicago, IL in the early 1970s and consistently pushes back against flat biographical readings of her work. [1] I have known Michiko Itatani since 1994 when she was my undergraduate advanced painting professor at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago where she has taught since 1979, yet I have only fragments of her story. Wishing to keep her life as a person and teacher private and separated from her work however difficult or impossible the task that may be, Itatani has stressed to me over the years, “I’d like to be remembered only by my work.” [2] This essay will simultaneously attempt to comply with her wish to “disappear” and also paint a portrait of the artist by analyzing two paired exhibitions of her work in Chicago. These exhibitions include her solo show Starry Night Encounter at Linda Warren Projects held September 9–October 22, 2016, which featured 28 large-scale and 65 smaller format paintings created since 2014 and Hi-Point Contact at the Zhou B. Art Center, a retrospective look at 23 of Michiko Itatani’s works from 1976 to the present curated by Sergio Gomez, which ran from October 17–December 30, 2016 filling an entire floor of a 14,000 square foot warehouse gallery at Zhou B. Art Center in Chicago.

Listen to Michiko Itatani introduce her exhibition Hi-Point Contact at the Zhou B. Art Center.

Itatani’s paintings are concerned with the infinite as well as the finite, “digested through personal experience.” [3] She explained her artistic process in a November 18, 2016 interview with art historian Jason Foumberg at the Zhou B. Art Center, held in conjunction with her Hi-Point Contact retrospective:

“Before I came to this country, I never thought art was my calling. I wanted to be a fiction writer. I still believe in fiction’s ability to tell the truth. Now I am writing with paint.”[4]

Listen to Michiko Itatani explain how fiction writing influences her painting.

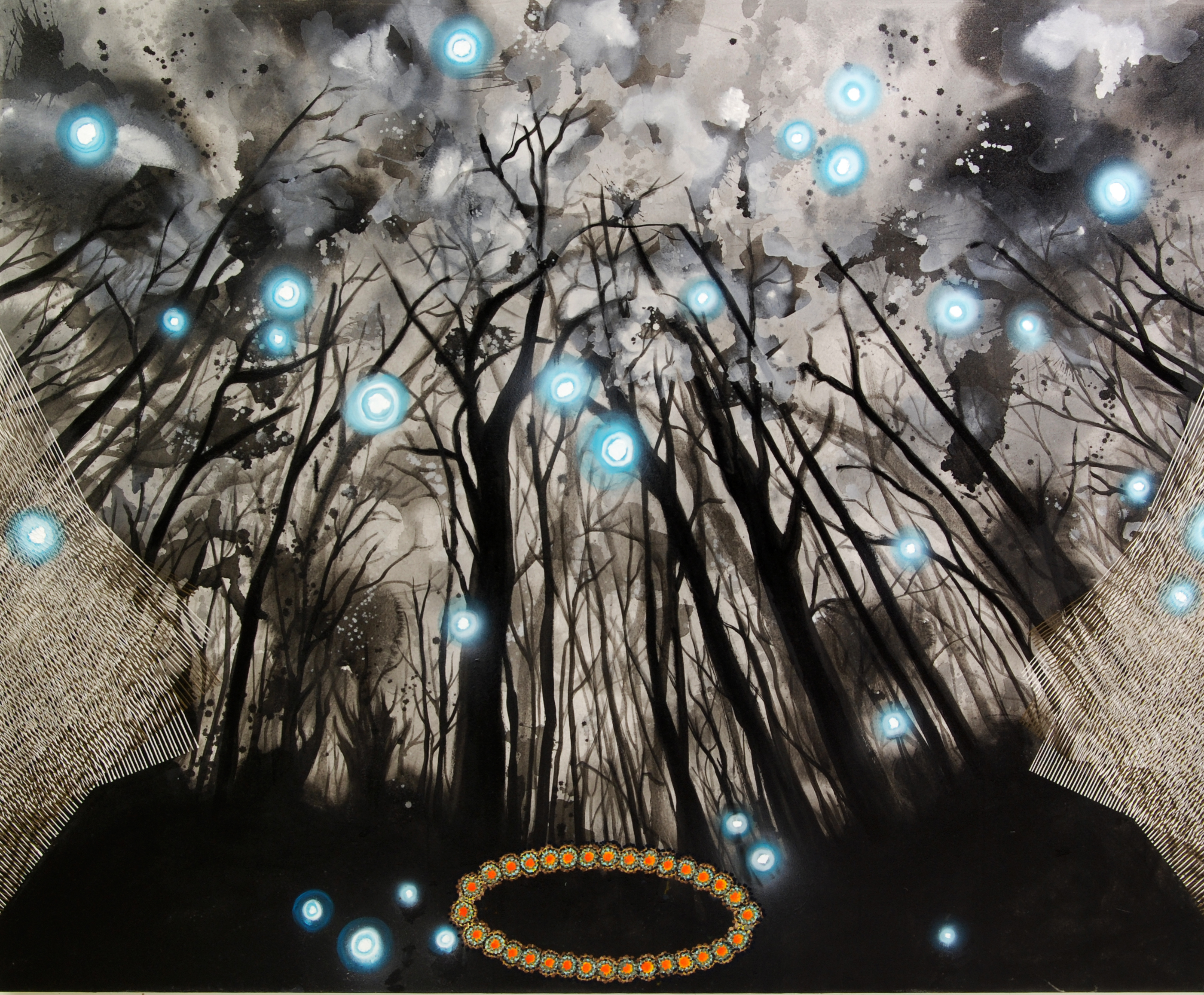

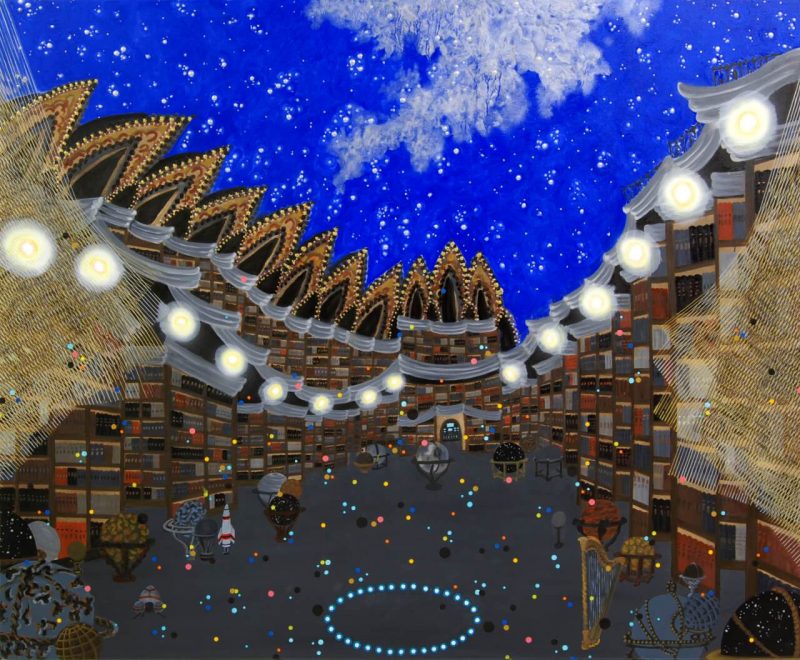

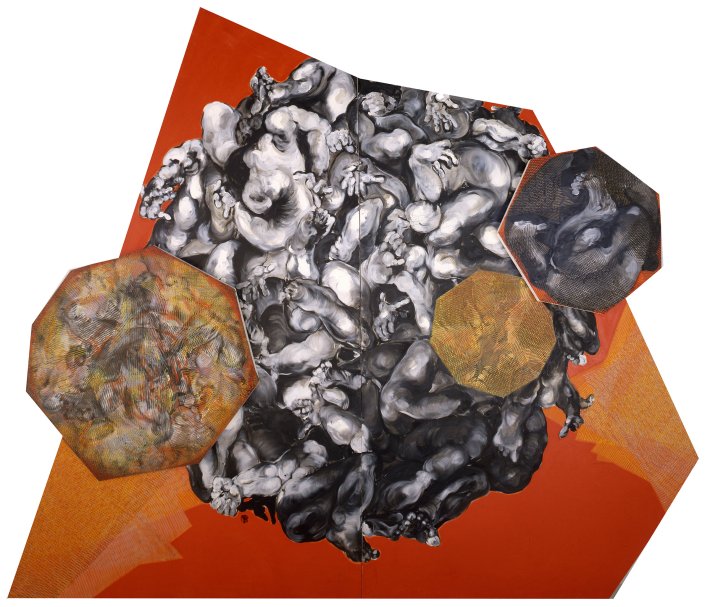

Michiko Itatani explores seeming binary themes—macro/micro, body/spirit, abstraction/figuration. Mixing modalities of painterly styles and spinning the viewer through hybrid and liminal spaces, her works take us to outer space; night scenes in a quiet forest, cathedral, or library; cosmic galactic battles; or inside of the human body. Inspired by science fiction, quantum mechanics, and physics, she evokes visions of a parallel universe to our own. Glowing rings of light have been a reoccurring theme in her works from the past decade. I imagine these might be portals for us to jump to another universe or perhaps they are landing signals or maybe a ritual gathering of spirits. The exact meaning of her work is left intentionally ambiguous. By using flat geometric shapes and thickly painted graphic marks, Itatani also calls attention to the surface and flatness of her canvases, reminding the viewer of the painting’s objectness thus breaking any illusion that we are fully entering into another world. Through dramatic shifts in scale from mural sized 19.5-foot-long paintings, such as her 1988 Raised & Supported (fig. 2), to miniature 5” x 5” paintings (fig. 3), she reminds us of our human scale and presence.

Although the appearance of her work has changed over the years—from her achromatic minimalistic and installation works in the 1970s and1980s, which she described as “cool abstraction,” an offshoot of De Stijl’s “Art Concret” geometric abstraction [5] (fig. 4), to her shaped canvases and massive figurative paintings of the 1990s, and the cosmic-themed pictorial and narrative works of the past decade that mix all of the aforementioned styles—her basic concerns, Itatani writes, “have always been consistent, always personal and humanistic.” [6] She notes:

“Using fictional and symbolic space, in which I condense experiences and imagined multilayered events, I am examining the issues of the human body and the cosmos, flesh and technology, the individual and the State, desire and choice, taboo and obsession.”[7]

Michiko Itatani was born in 1948 in Japan [8] and received her MFA in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is currently a professor. Itatani’s work has been seen in more than 100 solo and group exhibitions nationally, and internationally and can be found in such prestigious collections as Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea; Museu d’art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), Spain; and Tokoha Museum, Shizuoka, Japan.

Michiko Itatani was born in 1948 in Japan [8] and received her MFA in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is currently a professor. Itatani’s work has been seen in more than 100 solo and group exhibitions nationally, and internationally and can be found in such prestigious collections as Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea; Museu d’art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), Spain; and Tokoha Museum, Shizuoka, Japan.

Itatani has been the recipient of numerous awards and honors including the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, the Union League Club of Chicago’s “Distinguished Artists” Membership Award, the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Artist’s Fellowship, and the Marie Sharp Walsh New York Studio Grant, among others. [9]

Selected biographical timeline*:

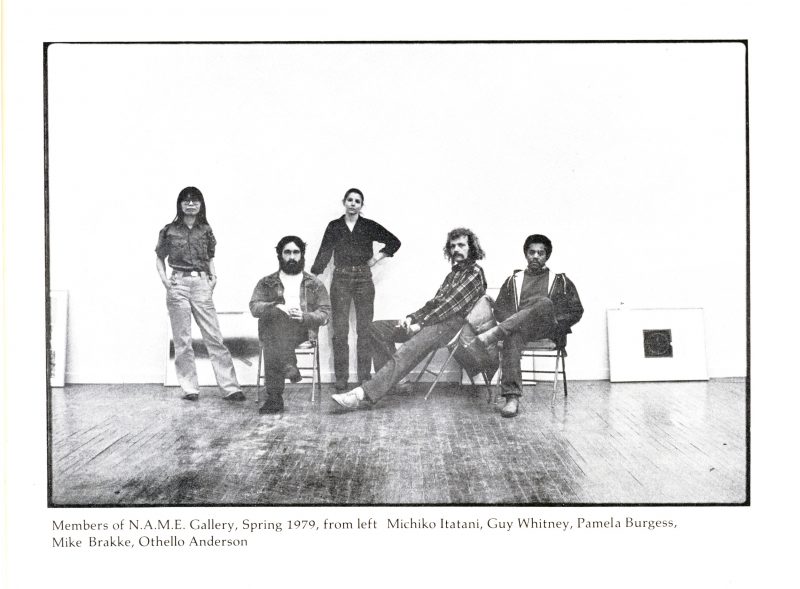

1970s-1980s N.A.M.E. Gallery member

1974 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture

1979-present Professor, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago

1980 National Endowment for the Arts, Artist’s Fellowship

1990 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship

2004 Union League Club Distinguished Artist Member

*This is a selected biographical timeline out of respect for the artist’s privacy and wish to be known specifically for her artwork. A more complete biography is available through: Jules Heller and Nancy G. Heller, North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary edited by (New York: Routledge, 1997), 1937–1938.

Foumberg aptly described Michiko Itatani as a “quiet giant” [10] of Chicago’s art scene for her self-effacing modesty in contrast with her outsized influence on generations of Chicago artists, including myself. Itatani’s career spans from 1973, when she first began exhibiting, to 1979, when she became a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), to the present.

Itatani studied literature and philosophy at a small liberal arts college near Kobe, Japan, after which, as other Japanese women artists such as Yoko Ono and Yayoi Kusama had in the 1960s, Itatani left her native country in the early 1970s. In a January 2016 interview in her studio she told me she came to Chicago “quite arbitrarily by pointing at the center of a map of the US.” Initially Itatani thought she was just going to “take a break from writing” when she arrived as a BFA student at SAIC but she went on to earn her MFA in 1976 from SAIC, and has since had over 100 solo and group exhibitions both nationally and internationally. [11]

Selected Map of Exhibitions and Publications

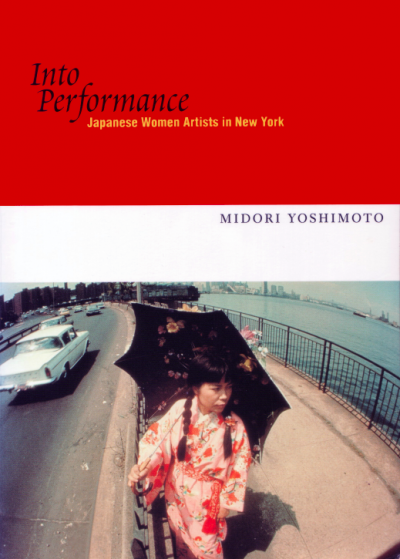

Michiko Itatani’s migration story is part of a larger wave of immigration to the US from Asia, Mexico, Latin America, and other non-Western nations that followed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) and the loosening of national origin restrictions and quotas that had been in place since 1924. While significant groups of Japanese, including artists and craftsmen, had immigrated to the Americas beginning in the 1880s, as part of large-scale agricultural labor migration to Hawaiʻi and the western US and Latin America, immigration to the US was largely blocked between 1924 and 1965 by The Immigration Act of 1924. Michiko Itatani’s narrative is also part of a longer Japanese history of artists who chose to live and work in the US. [12] While male Japanese expatriate artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, On Kawara, and Hiroshi Sugimoto have begun to enter the canon of Western art history, scholars, such as Midori Yoshimoto, have just begun to fill the historical gap concerning their female counter parts. Yoshimoto’s publication Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York examines the careers of Japanese women artists who came to New York in the 1960s such as Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Takako Saito, Mieko Shiomi, and Shigeko Kubota. [13] Far less has been written about Japanese women, such as Michiko Itatani, coming to the Midwest in the post-war years. Although Itatani remains based in Chicago, her wanderlust takes her routinely to New York to visit galleries and museums. She also travels extensively to Europe, Japan, and China to gather inspiration. Not one to limit influences for her paintings, Itatani cites Asian and Western art, architecture, music and history; literature; science; current events; and personal and collective tragedies as inspiration.

Looking Back to Look Forward

In 2011, critic Robin Dluzen’s catalog essay for Itatani’s Cosmic Kaleidoscope exhibition at Linda Warren Projects in Chicago, IL described how Itatani’s paintings are a continuation of her work as a writer: “The artist often refers to her oeuvre as resembling the path of a novel, each body of work acting as a sort of ‘chapter’ in an overall plot, and her ‘novel’ continually grows richer as more chapters are composed.” [14] In this way, her two-part exhibitions Starry Night Encounter and Hi-Point Contact form the latest chapters of Itatani’s painted novel.

The title “Starry Night Encounter” is her personal translation of the Japanese term “ichi-go ichi-e” ( 一 期 一 会 “one time, one meeting”), [15] Michiko Itatani writes in her artist statement:

It is an idea found in Zen Buddhism and in the concept of the transitory nature of things. The term is particularly adapted in the Japanese tea ceremony: a 7’ x 7’ space, a guest, a simple serving of tea.

One should delight in each encounter as if it were a “once-in-a-lifetime” occurrence. Treat every meeting as if it is the first and the last because it may not come again, or the same meeting repeats infinite times.

In my recent work, I am going back to this very basic feeling in a personal way. Using a fictional and symbolic space, I condense experienced and imagined multilayered encountering events. I appreciate every encounter with a person, a creature, a tree, a flower, a rock, a room, a book, a song, a painting or a life. [16]

This Zen Buddhist concept of “ichi-go ichi-e” is a guiding philosophy for Itatani’s work that can be seen even at the beginning of her career in 1979 in an essay published through N.A.M.E. Gallery.

Itatani’s guiding philosophy of “Ichi-go Ichi-e” ( 一 期 一 会 “one time, one meeting”), which comes from the Zen Buddhist tea ceremony tradition, can be seen in a 1979 N.A.M.E. Gallery Art Book 2 exhibition in Chicago that Itatani curated along with two other fellow N.A.M.E. Gallery members Michael Brakke and Austė. N.A.M.E. Gallery (1973–1997) provided “an association of visual and performing artists residing in the Chicago area” with an important alternative space. [17] Itatani was making monochromatic conceptual drawings, site-specific installation art (fig. 4), and what she said was called New York-style “cool abstraction” in a city that was more enamored with the Hairy Who and Chicago Imagist with their quirky, gritty, colorful, and cartoon styles inspired by outsider art. “In the 1980s, there was just Phyllis Kind Gallery in Chicago and she featured Chicago Imagists,” Itatani remembered. Although she was not a founding member of N.A.M.E. Gallery, she fondly recalls working closely for a decade “with other artists to create this space to have an alternative for other types of works.”[18]

In the 1980 Art Book 2 catalog, Itatani asked ten of the twenty-three featured artists to write on themselves for her contribution to the catalog. Her section of the catalog is a noticeable departure from her two colleagues who presented their artists’ images along with their statements or other creative writing by the artists in a punk graphic design aesthetic.

For my section of this book I asked ten artists to do writing pieces. It seemed to me that their attitude toward art, especially in relation to living, has something in common with mine. For me, to be an artist is an intellectual choice and a carefully chosen commitment. There is no intoxication. [19]

The first of the ten artists she invited featured a fictional Japanese scholar named Kageyama Riyo whom Itatani had asked to write about a fictional late artist named Satoh Boku. She went so far as to pen the essay in Japanese, asking the book’s copy editor, art critic Victor Cassidy, to assist her with translation. Satoh Boku, who we can assume was Itatani’s alter-ego, “was born in 1905 as the only son of the Noh Master Kyuma, the founder of Satoh Noh.” Boku was steeped in traditional Japanese arts and Noh theater training but he, like Itatani, “had interests and talents in other fields.” Itatani, as Kageyama Riyo, weaves a tale of a young man who is drawn to Western art, music, and writing and is on the verge of creating “revolutionary change in musical concepts in Japan after World War II.” But instead of realizing his potential, after the war he stops composing altogether and retreats back into the world of Noh theater and “unlike his father who had been an innovator, Boku took a rather conservative and traditional attitude toward Noh.” When Boku is said to have died in 1964 (when Itatani would have been sixteen), his notebooks, scores, and manuscripts for Ichigo Ichie, a vocal, instrumental, and dramatic work, and Zaboroku, a book of aesthetic investigations are discovered. [20] What Kageyam Riyo goes on to write about is a summary description, replete with diagrams, of these lost potential masterpieces that bare an eerie prediction for Itatani’s oeuvre thirty-seven years later.

In this fictional writing, which can be said to be a piece of conceptual art, we see the solitary road map Itatani laid for herself as an artist, including an avoidance of being distracted by trends and developing a philosophical manifesto for her practice. Even the title “Ichigo Ichie,” which she tells us in 2016 has been translated as “Starry Night Encounter,” is a foreshadowing to her work to come in 2016. “To all appearances, Ichigo Ichie was a strictly personal work that was never intended for public performances. Many parts are beyond the human capacity to perform ordinarily…,” the fictional Riyo writes of the fictional Boku’s work. In Ichigo Ichie, Boku revealed his belief in the dialectical universe and his capacity to work logically within his own value system. Using his study of Japanese esthetic terms as source material, he systematically tried to include all of his ideas in a single piece. Boku detached Ichigo Ichie from his audience completely and deliberately in order to avoid unnecessary confusion with other value systems. However, he related his work to the larger world by connecting the sphere of Ichigo Ichie to other more established spheres represented by Japanese esthetic terms (yugen, sabi, aware etc.) Ichigo Ichie was Boku’s private universe. It was a model of his existence. [21]

Ichi-go Ichi-e has also been Itatani’s model for existence as she continues to paint her cosmic novel one encounter at a time.

The selection of new works in Starry Night Encounter at Linda Warren Projects continued from her ongoing series or “chapters” from the past decade, including Cosmic Wanderlust (2010), HyperBaroque (2008), Cosmic Theatre (2006), and Personal Codes (2010) (fig. 8–10). Although this new work shares the same cosmic pictorial vocabulary of earlier works, what has changed in paintings such as Polaris from the series Encounter 16-B-1 (fig. 10) is a sense of urgency in her use of gesture and relative economy in her painted marks that I read as embracing freedom, or perhaps resigning herself to intentional failure, collapse, and decay. I say “relative economy” because of the sheer variety of marks Itatani uses to apply sumi ink and oil paint—from syringed line work and airbrushed light orbs, to calligraphic washes of ink and all manner of brush work possible from the industrial brushes she picks up at Home Depot (her preferred store for art supplies).

When I had visited her warehouse studio/home in the Andersonville neighborhood on the North Side of Chicago on January 21, 2016, I’d seen many of these works in progress and they reminded me of spectacular and kitschy galactic encounters with aliens from popular culture (e.g., Close Encounters of a Third Kind and the Star Wars film series). Although Itatani says these films did not directly influence her, she is an avid science fiction fan and there is a youthful playfulness in her expressionistic use of massive drips, letting the underpainting show through, and large graphic flat expanses of color. In reading her Starry Night Encounter artist statement in which she talks about ichi-go ichi-e and “going back to this very basic feeling in a personal way” appreciating “every encounter with a person, a creature, a tree, a flower, a rock, a room, a book, a song, a painting, or a life,” [22] I experienced a time warp, imagining Itatani looking back on her own artistic origins and youth and beginning to come to terms with her painting practice and her own place in the universe.

Itatani is intensely private about her past and family in Japan, sharing only the broad contours of her biography and the minimum information necessary to understand her paintings. Her mother was from a strict Zen Buddhist family and she had Itatani study calligraphy and the tea ceremony from an early age—influences that remain foundational to the artist’s creative practice [23] Itatani’s Starry Night Encounter statement inspired by the Zen Buddhist tea ceremony philosophy is reflective of her description of the process of making one of her earliest paintings. In describing her 1976 painting Untitled (fig. 11), which was the first painting included in her Hi-Point Contact retrospective, Itatani notes that she was “dragging her past” with her. Calligraphy, tea ceremony, and Zen Buddhist philosophy are “already still in that painting—it’s a 7 feet by 7 feet space, which is [a] two tatami mat space.” She made several dozen similar works at the time and recalls placing the painting on the floor, wetting the canvas with water and then adding and removing pigments each day [24] in a “ritualistic activity, just like a tea ceremony,” and that the painting was “about encounter in the small tea room. I think the idea of tea ceremony is just serving a cup of tea. That’s the starting point of that painting.” That same spirit from her early work is present in her paintings to this day. [25]

Listen to Itatani talk about the process of making her 1976 painting Untitled.

Japanese Esthetics

As a young artist, Michiko Itatani was aware of the Japanese avant-garde Gutai and Mona-Ha movements and has specifically cited artists Yoko Ono, Atsuko Tanaka, and Nobuo Sekine as early influences. [26] As previously noted, the artist was also inspired by her Zen Buddhist family and training in Japanese traditional arts such as calligraphy and tea ceremony.

In his 1996 exhibition essay, art critic Donald Kuspit quotes Itatani as embracing “Japanese esthetics of simplification and symbolization,” which she finds evident in “Noh theater and the stone gardens of Zen temples,” in her paintings. [27] As many critics have done, he grappled with the impact that living in the US has had on her work and read her paintings through an East versus West framework.

Itatani’s art is in the forefront of the new postmodern Japonisme. Its Japanese sense of concentration and Western sense of drama show us that we need the traditional fusion of the esthetic and the spiritual to save Western art from self-defeat—to rescue it from its cynical, decadent cul de sac. But it may be that Japanese esthetic spiritualism needs to latch on too profane Occidental art to save itself, for Japan (and the Orient) is becoming more and more modernized, to the extent that it may altogether lose its traditional esthetics, so crucial to generating a sense of the sacred. [28]

Written at the height of multiculturalism in the US and during Japan’s “Lost Decade” of economic downturn in the 1990s that followed the burst of an inflated real estate market, Kuspit’s statement is an oversimplification of complex cultural and global economic dynamics at best and Orientalist at worst. Kuspit’s analysis seems to hold on to a Western turn of the last century of the floating world fantasy of Japan as portrayed in Edo period (1603–1868) Japanese wood block prints, where Japan isolated from the West and modernism and post-modernism is incompatible with “traditional aesthetics” and a “sense of the sacred.” While there may be a grain of truth that Itatani employs Japonisme aesthetics for a Western audience, she has clearly stated that she is a “made in America artist” from Japan [29]—always positioning herself in the contemporary moment and inspired from a range of influences.

The Western Cannon, Literature, and Science

Itatani places emphasis on how Western art history is present in her work. She draws inspiration from the works of Michelangelo, sixteenth and seventeenth century Mannerism, seventeenth and eighteenth century Baroque art and architecture, twentieth century modernist abstract painting, and contemporary art. Itatani has traveled extensively in Central Europe, where she studies architectural spaces for her paintings on libraries and theaters, such as Starry Night, a painting from the series Encounter 16-B-5 (2016) (fig. 12). She makes sketches on site and later transforms them in the studio with the hopes “that viewers associate with their own space they experienced. All my recognizable images are [a] ‘lure’ to invite viewers’ participation.”[30] Above all, it is reading that has had the deepest impact on Itatani’s practice of “writing with paint.” She is a voracious reader, taking notes on books and turning them into diagrams of ideas. She reads widely but favors novels, science fiction, and books on math, philosophy, cosmology, and science—especially quantum mechanics and physics. When I visited her studio in January 2016, she was reading one book to teach herself how to play chess and three other physics books by Leonard Susskind. On her love of science, she has said, “If I could go back to my young age and restart my life, I think that’s the direction I’m going. I still feel becoming an artist is still very awkward. Although I have been doing this for such a long time, but once in a while I feel like I am in the wrong field.” [31]

Process

The ideas and the content of Itatani’s work come from her daily life—personal experiences and observations as well as from current events and the media. Once an issue begins to trouble her, it then becomes a focal point that sets the artist off on her research.

Before I start my painting, in front of me there are lots of things—articles, images, and I do diagrams. I still do, almost like writing a novel, I itemize things—what is important. I make a diagram of some thought [that] I want to focus on and then I have some idea of how I’m going to visualize that and usually what happens is even [if] I kind of know what I’m going to do, usually I end up doing something else. Unpredictability of making art somehow grabbed me in from the very beginning. [With] writing I was much more meticulous, planned, and structure in such a way. I thought painting [was] going to go in the same way…but I usually end up doing something else. [32]

A Self-Portrait of Sorts: HyperCharge

At the Zhou B. Art Center in the second segment of her two-part exhibition, Michiko Itatani continues to question “human existence in the larger context of the universe.” [33] She writes in the exhibition catalog:

“Hi-Point Contact is my fiction writing: incomplete, fragmented and under inquiry.”

Listen to Itatani describe her work HyperCharge.

Both exhibitions featured large-scale metaphorical self-portraits titled HyperCharge from Encounter HCE-1 (fig. 13) at the Zhou B. Art Center and from Encounter HCE-2 at Linda Warren Projects (fig. 14).

In Hypercharge-Encounter HCE-1 (2015) (fig. 13), the final piece featured in her retrospective, Itatani portrays herself as a white sperm whale, gesturing both to Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and her life-long interest in literature and to the muscular arms and legs from her figurative work from the 1990s that recall the figures in Michelangelo’s famous 1512 Creation of Adam fresco panels in the Sistine Chapel. In this early figurative work, she had attempted to use a body “that was genderless, ageless, and had no race” as a stand in to represent the struggles of human kind. She laughs that she “miserably failed” at her attempts to create a universal symbol: “Everyone thought it was a white male.” In a November 18, 2016 interview, Foumberg asked her how she relates to Moby Dickto which Itatani responded, “It’s not a direct connection but I am dealing with unattainable desire, disproportionate ambition.” [34]

With Untitled from the series Tolerance Zone #1, Itatani/Moby Dick/humankind rises from turbulent inky black waters towards a cosmic horizon filled with shooting stars in the form of a deconstructed American flag. Swimming towards the stars and stripes, the painting is a metaphor for Itatani’s own migration story. Geometric sheets of grated lines—the artist’s signature abstraction for writing—angle in on both sides of the picture plane. These angled parallel line forms have been present in her work for over forty years.

I write in English now but I started in Japanese. Japanese goes that way. I write [in a] linear way but I always write several different angles. The lines become curtains, safety net, sound…they change according to the painting. It’s one of the “abstract” elements, so you can read it as you want. [35]

On the right-hand side, a curtain of lines cloak a globe or planet shape—another recurring iconic Itatani symbol first seen in her Cosmic Theater series (2006). A ring of blue lights, a reference to her Personal Codes series (2009), opens a potential portal to another universe at the bottom of the canvas.

These compositional elements are repeated in Hypercharge-Encounter HCE-2 (2015) (fig. 14), but now a silhouette of a missile or perhaps a cartoonish space rocket rises from the ocean (Itatani has included toy models of Cold War missiles in other works). The viscerally painted sumi ink and oil gestures in the sky give way to a galaxy, and reference her Cosmic Wanderlust series (2013) (fig. 16). In the wake of the devastation of the March 11, 2011 Tohoku earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the subsequent loss of her mother shortly thereafter, Itatani was inspired to create the Cosmic Wanderlust series. [36] The title of these works “HyperCharge” references her 1996 work of the same title. In the work, the stars and stripes of the earlier painting have disintegrated and the viewer is left with remnants of lens and solar flares. The title of the Zhou B. Art Center exhibition, “Hi-Point Contact”—an “engineering term describing a momentary touching of two elements”—is also a reiteration of a subtitle she used for a suite of paintings in the 1990. Itatani carries the past with her in her densely-layered symbolism or what she calls “codes” and “ciphers.” [37]

Turning Catastrophe into Creativity

In addition to Japanese traditional and avant-garde influences and her Western art training, catastrophic events, be they personal events, wars, or natural disasters, have also been influential in shaping Michiko Itatani’s work in its form, subject, and narrative.

On Working Large

Itatani’s paintings are monumental in size—at times approaching the size of murals as in her 19.5-foot long 1988 Untitled painting from Raised & Supported (fig. 17). When I asked her why she paints at such a scale she said, “Because I was sick as a child….I could never complete a marathon.” She explained that in Japan kids would have all of these sports competitions and she would just faint. Her parents did not think she would make it to an adult age, “but here I am” she laughs. [38] Painting large is about the physical challenge for Itatani, so she insists on making her own stretchers from beginning to end—going to the lumber yard, working in her woodshop with her table saw in the back of her studio to build the stretcher, and then stretching and gessoing the canvas. “Physicality is a very different thing than my writing experience,” she told Foumberg in their interview.

She also notes: “In the 1970s at SAIC [we had] nothing to look forward to. [The] art scene was quiet and I wanted to shoot the moon!” This was an era where painting was still fighting proclamations of its death [39] and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty earthwork gave scale a whole new meaning for artists. So Michiko Itatani and her peers at SAIC began to paint big and, still as ambitious as she was in her twenties Itatani says, “I just never stopped.” [40]

Embracing Failure and Final Words

Listen to Itatani introduce her Moon-light/Mooring series.

She did almost stop once, however. After 9/11, Michiko Itatani decided it was time to quit painting. She felt she had accomplished all she had set out to do, and demoralized by the weight of the devastation, she was thinking that art was “such a self-indulgent activity and that perhaps” she “should do something more useful.” In 2009, with her Moonlight/Mooring series (fig. 18–20), she set out to make a “series of final works of my life.” [41] Personal Codes from Moonlight/Mooring MM-1 (fig. 19) and Personal Codes from Moonlight/Mooring MM-2 (fig. 20) were to be the last two pieces in this final series. But thankfully she found that she could not stop painting. [42] At her November 18, 2016 artist talk at the Zhou B. Art Center, she reflected on this near brush with the death of her own painting. Her talk was held ten days after the nation was shaken up by the controversial 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump. The gathering that night was also four days after witnessing the biggest and closest super moon since 1948—an event, which Itatani reminded the audience, helped put the outcome of the election and its consequences in perspective.

Basically, I am interested in the human existence in the larger context of the universe…super moon was [just here] and I was looking at our moon, which is a little larger looking a couple of days ago. When you really think about it, if the moon is a little bit smaller, earth doesn’t exist this way…it’s really amazing we are here in this condition on this earth and we are doing what we are doing and I’m painting—such a precious, precious experience we are having and we are killing each other. That’s something I always think about it. Human beings are self-centered, greedy, and violent, and when I realize I’m one of them, I really have to think about what I like about us. [43]

When she was making Personal Codes from Moonlight/Mooring MM-1 and Personal Codes from Moonlight/Mooring MM-2 Itatani was trying to reconcile the events of September 11, 2001.

“After all these things, I have to love myself. I have to love our species. So I started to count what I like about us and it come down to art, in a larger way—from music, to writing, to movies, to theater, to something creative, including science.”

She opted for optimism, even if it’s false, and to “celebrate the act of creation.” [44]

Listen to Itatani describe her Personal Codes paintings.

Itatani’s work is a celebration of creation that embraces failure. “Do you have a favorite painting in the show?” Foumberg asked her to reflect on her retrospective. Itatani laughed and confided:

I think maybe each time I come, I hate another painting. Others are OK but I always hate one painting whenever I come…I’m not exactly satisfied with what I’ve done so far. That’s one reason I can go back to my studio tomorrow and challenge. That’s my life.

And I realize I’m not going to be here forever and making a painting. I don’t talk about teaching too much but it’s important, in a way. I know I cannot finish my project so I am counting on you, younger people. That’s one reason I still feel very enthusiastic about handing down what I know to the next generation. [45]

Writing as an artist trained by Itatani, I hope this essay will begin to open up an understanding of her oeuvre for the next generation. I will close using Itatani’s own words to underscore the interconnected nature of her painted cosmic novel, “most of my work is related to my personal experience and thoughts in fictional form….Strangely, all connect at the end (my failed attempt to quit art/tsunami/nuclear event/mother’s death/examination on my childhood).” [46]

About the Curator:

Laura Kina is an artist, scholar, and educator based in Chicago. Asian American studies, contemporary Asian American art, Critical Mixed Race studies, and feminist/queer theory form the nexus for her intersectional scholarly research, publications, and projects. Kina is Vincent de Paul Professor of Art, Media, & Design and Director of Critical Ethnic Studies at DePaul University. She earned her MFA in Studio Art from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2001, where she studied with painters Kerry James Marshall and Phyllis Bramson. Kina earned her BFA in painting and drawing in 1994 from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she studied with painters Michiko Itatani and Ray Yoshida.

Kina has exhibited nationally and internationally in galleries and museums including: the Chicago Cultural Center, India Habitat Centre, India International Centre, Japanese American National Museum, Nehuru Art Centre, Okinawa Prefectural Art Museum, Rose Art Museum, Spertus Museum, and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience. Her work is featured in Sugar/Islands: Finding Okinawa in Hawaiʻi – the Art of Laura Kina and Emily Hanako Momohara (Bear River Press, 2015).

Kina is the coeditor of War Baby/Love Child: Mixed Race Asian American Art (University of Washington Press, 2013) and Queering Contemporary Asian American Art (University of Washington Press, 2017). She is also the cofounder of the Critical Mixed Studies conference, journal, and association and a reviews editor for the Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas (Brill). Learn more about her work: https://www.laurakina.com

Acknowledgements:

The research and production of this exhibition module has been funded by a University Research Academic Stakeholders Grant from DePaul University, a Terra Foundation for American Art Chicago Art and Design 1871–2000 Academic Program Grant, and the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU. Kina would like to thank her DePaul University graduate research assistant Aiden Bettine for compiling the data for the exhibition/publication timeline and map, interactive designer Alexei Taylor for programming and designing the Itatani module, and Alexandra Chang for her editorial assistance.

Endnotes

[1] Biographical information sent in an e-mail to the author December 10, 2016.

[2] Email to the author, June 15, 2017.

[3] January 21, 2016 in-person interview with Michiko Itatani conducted by the author in Itatani’s studio/home in Chicago, IL.

[4] November 18, 2016 interview with Jason Foumberg at the Zhou B. Art Center in Chicago, IL in conjunction with the “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” exhibition. Audio recorded by Laura Kina and published by Sergio Gomez The Artist Next Level podcast “#089 Conversations between artist Michiko Itatani and art historian Jason Foumberg,” Accessed December 6, 2016. https://www.theartistnextlevel.com/089-conversation-artist-michiko-itatani-art-historian-jason-foumberg/.

[5] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview. “Cool Abstraction,” according to Edward Ragg in Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 2–3, is adapted “from the late 1940s and 1950s French art criticism” and “refers to the geometric ‘Art Concret’”—a movement termed by Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist and founder of De Stijl, in his 1930 Manifesto of Concrete Art. Ragg contrasts “cool abstraction” with “warm abstraction” which is, “more expressionist painting or any abstraction championing spontaneous creation of the ‘unformed’” (‘Art Informel’/Tachisme’).”; See “Art Terms,” Tate. Accessed July 3, 2017. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms.

[6] Artist statement, Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact exhibition catalog, (Chicago, IL: Zhou B. Art Center, 2016), 7.

[7] Artists statement, Michiko Itatani, Beaux-Arts Celebration 2004: Honoring Distinguished Artists Michiko Itatani and John David Mooney event booklet, (Chicago, IL: Union League Club of Chicago, 2004).

[8] Itatani has requested to be remembered only by her work and as such, has asked to keep her biography as private as possible including where she was born and raised and where she attended elementary school and college in Japan.

[9] Biography courtesy of the artist and Linda Warren Projects.

[10] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[11] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[12] For more on the Japanese Avant-garde see Alexandra Munroe “Japanese Artists in the American Avant-garde 1945–1970,” June 29, 1987 originally published in Contemporary Japanese Art in America 1: Arita, Nakagawa, Sugimoto (Japan Society, 1987). Accessed January 4, 2017. https://www.alexandramunroe.com/japanese-artists-in-the-american-avant-garde-1945-1970/.

[13] Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (Rutgers University Press, 2005).

[14] Robin Dluzen, “Cosmic Kaleidoscope” Catalog (Chicago, IL: Linda Warren Projects, 2013).

[15] According to Wikipedia, Ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会 “one time, one meeting”) is a Japanese four-character idiom (yojijukugo) that describes a cultural concept of treasuring meetings with people. The term is often translated as “for this time only,” “never again,” or “one chance in a lifetime.” The term reminds people to cherish any gathering that they may take part in, citing the fact that many meetings in life are not repeated. Even when the same group of people can get together again, a particular gathering will never be replicated and thus, each moment is always once-in-a-lifetime. The concept is most commonly associated with Japanese tea ceremonies, especially tea masters Sen no Rikyū and Ii Naosuke. Wikipedia, “Ichi-go ichi-e.” Last modified June 2017. Accessed July 3, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichi-go_ichi-e.

[16] Linda Warren Projects Press Release, Gallery X & Y: Michiko Itatani, “Starry Night Encounter” September 9–October 22, 2016.

[17] “N.A.M.E. Gallery,” The Frick Collection “Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America.” Accessed December 11, 2016. https://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=6129; Lynne Warren, “Art Centers, Alternative,” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed December 11, 2016. https://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/74.html.

[18] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[19] Michiko Itatani, “Part II Artists’ Writings,” in Art Book 2, ed. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste (Chicago, IL: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979), 131.

[20] Kageyama Riyo, “Satoh Boku” in Art Book 2, ed. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste (Chicago, IL: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979), 132-136.

[21] Ibid., 135–136.

[22] Ibid., Linda Warren Projects Press Release.

[23] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[24] Michiko Itatani “Untitled 1976” audio interview from the Vamonde app adventure “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” 2016.

[25] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[26] Liza Rush, “Michiko Itatani Interview” (Asian American Art Oral History, 2010). Accessed January 4, 2017. https://via.library.depaul.edu/oral_his_series/15/.

[27] Quoted by Donald Kuspit in his essay “Michiko Itatani’s Visionary Space” for Michiko Itatani: Close Binary exhibition brochure (DeKalb, IL Northern Illinois University: NIU Art Museum, Altgeld Gallery, 1996).

[28] Ibid., Donald Kuspit.

[29] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[30] Email to the author, December 12, 2016.

[31] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[32] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[33] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[34] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[35] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[36] I asked Itatani if the Cosmic Wanderlust series was directly inspired by the death of her mother. She acknowledged that her “CTRL-Home/Echo” series (of which the Cosmic Wanderlust sub-series is part of), “is in relation to what I went through during those time” but that she wrote the artist statement for this series in 2011, before her mother’s death. “Strangely, all connect at the end (my failed attempt to quit art/tsunami/nuclear event/mother’s death/examination on my childhood). ‘Cosmic Wanderlust’ is my state of mind.” Email to the author July 3, 2017.

[37] Michiko Itatani as quoted by Robin Dluzen in “Cosmic Kaleidoscope” catalog (Chicago, IL: Linda Warren Projects, 2013).

[38] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[39] The “death of painting” has been declared numerous times since 1839 when French painter Paul Delaroche saw the first Daguerreotype and reportedly said, “From today, painting is dead!” American sculptor and art critic Donald Judd’s declaration “it seems painting is finally finished,” a position her repeated in reviews in Arts magazine from the late 1950s and early 1960s, was still influential when Michiko Itatani was a young art student in the 1970s.

[40] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview. A significant caveat to Itatani’s practice of making mural sized paintings is that in the 1990s she found herself in intensive care following a head injury, which inspired her 1996–1999 Micro/Macros series that explored mediations on the inside of the body through abstraction. She thought she was at the end of her life at that time and began to think about how insignificant we are as human beings and at the same time how amazing it is to be alive. Unable to climb a ladder after the incident, she began to work on a very small scale. At first she tried to condense what she had been doing in her larger paintings but in her first 50 paintings she did not succeed and threw them away. She eventually did figure out how to work on a small scale and found in them an added benefit that she could give away smaller works when needed. Since the 1990s she has alternated between large and small-scale works.

[41] Michiko Itatani “Personal Codes & Earthlings” audio interview from the Vamonde app adventure “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” 2016.

[42] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[43] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[44] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[45] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[46] Ibid., Email to the author, July 3, 2017.

Bibliography

Dluzen, Robin. Cosmic Kaleidoscope, catalog. Chicago: Linda Warren Projects, 2013.

The Frick Collection. “N.A.M.E. Gallery.” Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America. Accessed December 11, 2016. https://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=6129.

Itatani, Michiko. “Part II Artists’ Writings.” Art Book 2, ed. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste, 131. Chicago: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979.

_____. “Artist Statement.” In Beaux-Arts Celebration 2004: Honoring Distinguished Artists Michiko Itatani and John David Mooney, event booklet. Chicago: Union League Club of Chicago, 2004.

_____. Interview with Laura Kina. Michiko Itatani studio, Chicago, IL, January 21, 2016.

_____. “Artist Statement.” Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact, exhibition catalog, 7. Chicago: Zhou B. Art Center, 2016.

_____. “Personal Codes & Earthlings.” Vamonde app adventure Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact 2016. Audio, https://www.vamonde.com/#/.

_____. “Untitled 1976.” Vamonde app adventure Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact, 2016. Audio, https://www.vamonde.com/#/.

_____. “#089 Conversations between artist Michiko Itatani and art historian Jason Foumberg.” Interview with Jason Foumberg. The Artist Next Level, November 18, 2016. Audio, 34:35. https://www.theartistnextlevel.com/089-conversation-artist-michiko-itatani-art-historian-jason-foumberg/.

Kuspit, Donald. “Michiko Itatani’s Visionary Space,” Michiko Itatani: Close Binary, exhibition brochure. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University: NIU Art Museum, Altgeld Gallery, 1996.

Munroe, Alexandra. “Japanese Artists in the American Avant-garde 1945–1970.” Contemporary Japanese Art in America 1: Arita, Nakagawa, Sugimoto. Japan Society, 1987. Accessed January 4, 2017. https://www.alexandramunroe.com/japanese-artists-in-the-american-avant-garde-1945-1970/ .

Ragg, Edward. Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Riyo, Kageyama. “Satoh Boku.” Art Book 2, eds. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste, 132-136. Chicago: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979.

Rush, Liza. “Michiko Itatani Interview,” Asian American Art Oral History, 2010. Accessed January 4, 2017.https://via.library.depaul.edu/oral_his_series/15/ .

Tate. “Art Terms,” Tate. Accessed July 3, 2017. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms.

Linda Warren Projects Press Release, Gallery X & Y: Michiko Itatani, “Starry Night Encounter” September 9–October 22, 2016.

Wikipedia, “Ichi-go ichi-e.” Last modified June 2017. Accessed July 3, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichi-go_ichi-e.

Warren, Lynne. “Art Centers, Alternative.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed December 11, 2016. https://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/74.html.

Yoshimoto, Midori. Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005.

[1] Biographical information sent in an e-mail to the author December 10, 2016.

[2] Email to the author, June 15, 2017.

[3] January 21, 2016 in-person interview with Michiko Itatani conducted by the author in Itatani’s studio/home in Chicago, IL.

[4] November 18, 2016 interview with Jason Foumberg at the Zhou B. Art Center in Chicago, IL in conjunction with the “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” exhibition. Audio recorded by Laura Kina and published by Sergio Gomez The Artist Next Level podcast “#089 Conversations between artist Michiko Itatani and art historian Jason Foumberg,” Accessed December 6, 2016. http://www.theartistnextlevel.com/089-conversation-artist-michiko-itatani-art-historian-jason-foumberg/.

[5] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview. “Cool Abstraction,” according to Edward Ragg in Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 2–3, is adapted “from the late 1940s and 1950s French art criticism” and “refers to the geometric ‘Art Concret’”—a movement termed by Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist and founder of De Stijl, in his 1930 Manifesto of Concrete Art. Ragg contrasts “cool abstraction” with “warm abstraction” which is, “more expressionist painting or any abstraction championing spontaneous creation of the ‘unformed’” (‘Art Informel’/Tachisme’).”; See “Art Terms,” Tate. Accessed July 3, 2017. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms.

[6] Artist statement, Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact exhibition catalog, (Chicago, IL: Zhou B. Art Center, 2016), 7.

[7] Artists statement, Michiko Itatani, Beaux-Arts Celebration 2004: Honoring Distinguished Artists Michiko Itatani and John David Mooney event booklet, (Chicago, IL: Union League Club of Chicago, 2004).

[8] Itatani has requested to be remembered only by her work and as such, has asked to keep her biography as private as possible including where she was born and raised and where she attended elementary school and college in Japan.

[9] Biography courtesy of the artist and Linda Warren Projects.

[10] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[11] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[12] For more on the Japanese Avant-garde see Alexandra Munroe “Japanese Artists in the American Avant-garde 1945–1970,” June 29, 1987 originally published in Contemporary Japanese Art in America 1: Arita, Nakagawa, Sugimoto (Japan Society, 1987). Accessed January 4, 2017. http://www.alexandramunroe.com/japanese-artists-in-the-american-avant-garde-1945-1970/.

[13] Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (Rutgers University Press, 2005).

[14] Robin Dluzen, “Cosmic Kaleidoscope” Catalog (Chicago, IL: Linda Warren Projects, 2013).

[15] According to Wikipedia, Ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会 “one time, one meeting”) is a Japanese four-character idiom (yojijukugo) that describes a cultural concept of treasuring meetings with people. The term is often translated as “for this time only,” “never again,” or “one chance in a lifetime.” The term reminds people to cherish any gathering that they may take part in, citing the fact that many meetings in life are not repeated. Even when the same group of people can get together again, a particular gathering will never be replicated and thus, each moment is always once-in-a-lifetime. The concept is most commonly associated with Japanese tea ceremonies, especially tea masters Sen no Rikyū and Ii Naosuke. Wikipedia, “Ichi-go ichi-e.” Last modified June 2017. Accessed July 3, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichi-go_ichi-e.

[16] Linda Warren Projects Press Release, Gallery X & Y: Michiko Itatani, “Starry Night Encounter” September 9–October 22, 2016.

[17] “N.A.M.E. Gallery,” The Frick Collection “Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America.” Accessed December 11, 2016. http://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=6129; Lynne Warren, “Art Centers, Alternative,” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed December 11, 2016. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/74.html.

[18] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[19] Michiko Itatani, “Part II Artists’ Writings,” in Art Book 2, ed. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste (Chicago, IL: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979), 131.

[20] Kageyama Riyo, “Satoh Boku” in Art Book 2, ed. Michael Brakke, Michiko Itatani, Auste (Chicago, IL: N.A.M.E. Gallery, 1979), 132-136.

[21] Ibid., 135–136.

[22] Ibid., Linda Warren Projects Press Release.

[23] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[24] Michiko Itatani “Untitled 1976” audio interview from the Vamonde app adventure “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” 2016.

[25] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[26] Liza Rush, “Michiko Itatani Interview” (Asian American Art Oral History, 2010). Accessed January 4, 2017. http://via.library.depaul.edu/oral_his_series/15/.

[27] Quoted by Donald Kuspit in his essay “Michiko Itatani’s Visionary Space” for Michiko Itatani: Close Binary exhibition brochure (DeKalb, IL Northern Illinois University: NIU Art Museum, Altgeld Gallery, 1996).

[28] Ibid., Donald Kuspit.

[29] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[30] Email to the author, December 12, 2016.

[31] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[32] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[33] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[34] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[35] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[36] I asked Itatani if the Cosmic Wanderlust series was directly inspired by the death of her mother. She acknowledged that her “CTRL-Home/Echo” series (of which the Cosmic Wanderlust sub-series is part of), “is in relation to what I went through during those time” but that she wrote the artist statement for this series in 2011, before her mother’s death. “Strangely, all connect at the end (my failed attempt to quit art/tsunami/nuclear event/mother’s death/examination on my childhood). ‘Cosmic Wanderlust’ is my state of mind.” Email to the author July 3, 2017.

[37] Michiko Itatani as quoted by Robin Dluzen in “Cosmic Kaleidoscope” catalog (Chicago, IL: Linda Warren Projects, 2013).

[38] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[39] The “death of painting” has been declared numerous times since 1839 when French painter Paul Delaroche saw the first Daguerreotype and reportedly said, “From today, painting is dead!” American sculptor and art critic Donald Judd’s declaration “it seems painting is finally finished,” a position her repeated in reviews in Arts magazine from the late 1950s and early 1960s, was still influential when Michiko Itatani was a young art student in the 1970s.

[40] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview. A significant caveat to Itatani’s practice of making mural sized paintings is that in the 1990s she found herself in intensive care following a head injury, which inspired her 1996–1999 Micro/Macros series that explored mediations on the inside of the body through abstraction. She thought she was at the end of her life at that time and began to think about how insignificant we are as human beings and at the same time how amazing it is to be alive. Unable to climb a ladder after the incident, she began to work on a very small scale. At first she tried to condense what she had been doing in her larger paintings but in her first 50 paintings she did not succeed and threw them away. She eventually did figure out how to work on a small scale and found in them an added benefit that she could give away smaller works when needed. Since the 1990s she has alternated between large and small-scale works.

[41] Michiko Itatani “Personal Codes & Earthlings” audio interview from the Vamonde app adventure “Michiko Itatani: Hi-Point Contact” 2016.

[42] Ibid., January 21, 2016 interview.

[43] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[44] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[45] Ibid., November 18, 2016 interview.

[46] Ibid., Email to the author, July 3, 2017.