Farewell to you,

Our friends so true;

May Love and Truth Eternal guide you,

And Love Divine

Upon your pathway shine,

Until we meet again.

—A.R. Zorn, Buddhist Prayer book [1]

Introduction

After the signing of Executive Order 9066, James Numata’s life path took an unexpected turn. A US citizen by birth, Numata moved as a child to Japan with his family. When he returned to the United States in 1940 before the war, he did so with his first wife Shizue, a Japanese education under his belt, and the rest of his family across an ocean. In the spring of 1942, Numata and his wife were forced to leave their southern California home and spend the war years in the Heart Mountain, Wyoming incarceration camp.

The terminology used to discuss the experiences of Japanese Americans during World War II is particularly charged because at the time the government and military often reverted to terms that minimized their actions and the infringement of civil rights. The exclusion orders, for example, did not refer to Japanese Americans born in the US as citizens but instead targeted “all persons of Japanese ancestry…both alien and non-alien.” Captions written for War Relocation Authority photographs reflect a similar avoidance of acknowledging citizenship as writers referred to Japanese Americans born in the United States as persons of Japanese ancestry. Inaccurate terminology is also reflected in the often-used word “internment” to describe the process of confining Japanese Americans during World War II. That term is largely inaccurate, however, as it refers to a legal process of detainment for non-citizens. In historian Roger Daniel’s essay on terminology he writes, “internment in the United States generally followed the rules set down in American and international law. What happened to those West Coast Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in army and WRA concentration camps was simply lawless.” [2]

Scholars have argued that euphemistic language has distorted this history. According to Raymond K. Okamura, euphemism “helped the government to maintain a decent public image…and kept the historical record in the government’s favor.” [3] In 2013 the national Japanese American Citizens League published a handbook on language use suggesting terms that should be used in place of euphemism citing that the government used language “to control public perceptions about the forced removal of Japanese American citizens from their West Coast homes.” [4]

Chart below from “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II,” National JACL Committee, April 27, 2013.

SUMMARY TABLE OF ACCURATE TERMS

The table below, constructed from Ishizuka’s list (Ishizuka, 2006, p.72), summarizes the various euphemistic terms and their more accurate counterparts.

EUPHEMISM ACCURATE TERM

evacuation exclusion, or forced removal

relocation incarceration in camps; also used after release from camp

non-aliens U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry

civilian exclusion orders detention orders

any or all persons primarily persons of Japanese ancestry

may be excluded evicted from one’s home

native American aliens renunciants (citizens who, under pressure, renounced U.S. citizenship)

assembly center temporary detention facility

relocation center American concentration camp, incarceration camp, illegal detention center, inmates held here are “incarcerees”

internment center reserve for DOJ or Army camp holding alien enemies under Alien Enemies Act 1798”

He left Heart Mountain more than three years later bound for a new life in Chicago. His story is not unlike the stories of other Kibei, or second generation Japanese Americans born in the United States and educated in Japan, except that when James Numata died in 1997, he had left behind 10,000 photographs that are now in the archives of Chicago’s Japanese American Service Committee (JASC). While the archive can give us only bits and pieces of Numata’s biography, it is a visual treasure trove that traces the contours of the world as Numata framed it with his camera. Those photographs give us a sense of his life before the war and of a burgeoning Japanese American community that formed in postwar Chicago. Despite the incarceration, relocation, and persistent discrimination, Japanese Americans in Chicago worked towards building the social and cultural connections that would make Chicago home.

Because photography involves mechanical reproduction and produces images that appear to replicate the subject represented, photographs can be mistakenly thought to be authorless mirrors. The term “photograph” itself means light writing, as if the photographer has little to do with the image created. But many scholars have fashioned theories of photographic meaning that acknowledge photographs as complex representations without fixed meaning. Cultural theorist Roland Barthes used semiotic theory to think about photographs as systems of meaning much like language. In that sense, one can read a photograph much like one reads a text. The photograph’s relationship to truth, and to its subject, is tenuous. Historian John Tagg argues that “every photograph is the result of specific and, in every sense, significant distortions which render its relation to any prior reality deeply problematic.” Photographic meaning shifts and is often dependent on context. As Graham Clarke writes, “Any photograph is dependent on a series of historical, cultural, social and technical contexts which establishes its meanings as an image and an object.” Photographs can serve as important primary sources and, although they might look like windows onto the past, they require a high level of scrutiny and analysis just as any other primary source does.

When analyzing photographs as visual representations, here are some formal elements that might be worth considering:

Cropping

Frame

Flatness

Space

Format

Scale

Angle of Vision

Perspective

Time

Movement

Light

Exposure

Print

Focus

Color

Detail

Trick effects (multiple negatives, photoshopping, etc…)

Neutrality/Reality

Pose

Objects

Aesthetics

Sequence

When analyzing photographs as visual representations, here are some contextual questions that might be worth considering:

What is this photograph of?

• What is the denoted (literal) meaning?

• What are the connoted (symbolic) meanings?

Of what is the photograph a product?

• Who made the photograph?

• For whom was it made?

• Why was it made?

• When was it made?

• What is the relationship between photographer, subject, and viewer? Is there an (un)equal balance of power?

• Are technical concerns relevant?

• Are there any political or ideological motivations?

In what context are you viewing it?

• What was the original context and rhetorical function of its making?

• Does it belong to a sequence of images?

• Does it belong to a recognizable genre of image?

• Is there any written text associated with the image? If so, what is the relationship between the written text and the image?

Is there anything about the photograph that you can’t explain?

• What questions do this image raise?

• What categories of historical analysis are relevant to the image? Labor, race, gender, war, politics, domestic life, immigration?

For more on photography and meaning see:

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: The Noonday Press, 1988.

Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

Berger, John. Understanding a Photograph. Aperture, 2013.

Clarke, Graham. The Photograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Lutz, Catherine and Jane Collins, “The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes,” in The Photography Reader, ed. Liz Wells (New York: Routledge, 2003), 354-374.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

Sturken, Marita. “Camera Images and National Meanings,” in Tangled Memories. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, 19-43.

Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Numata used the camera to construct a particular vision of postwar life. This essay argues that his photographs of Japanese Americans in Chicago create a visual language of affirmation that implicitly rejects the US government’s plans for ethnic dispersal. Numata does not depict dislocation, anger, and frustration. His images do not explain what brought its subjects to Chicago. Rather, he uses the camera to avow and codify the status of Japanese Americans as workers, as business owners, as church-goers, and social club members, as well dressed, and made up, and healed and whole. The photographs reweave Japanese Americans into the civic fabric of urban life on their own terms and in ways that did not contest existing normative patterns of gender or class, but that did provide a vehicle to visualize community and normalcy with smiles, parties, light, and shadow.

Before the War: Numata in Japan

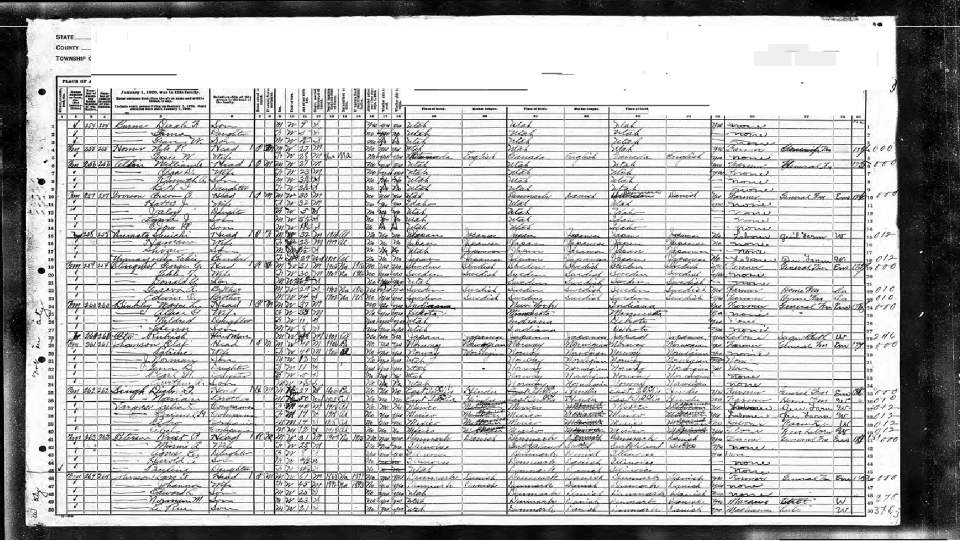

James Numata was born on March 27, 1918 to Shuichi and Hamano Numata (fig. 1-2). The family spent the first seven years of James’ life living in northern Utah, raising James and his two younger siblings.

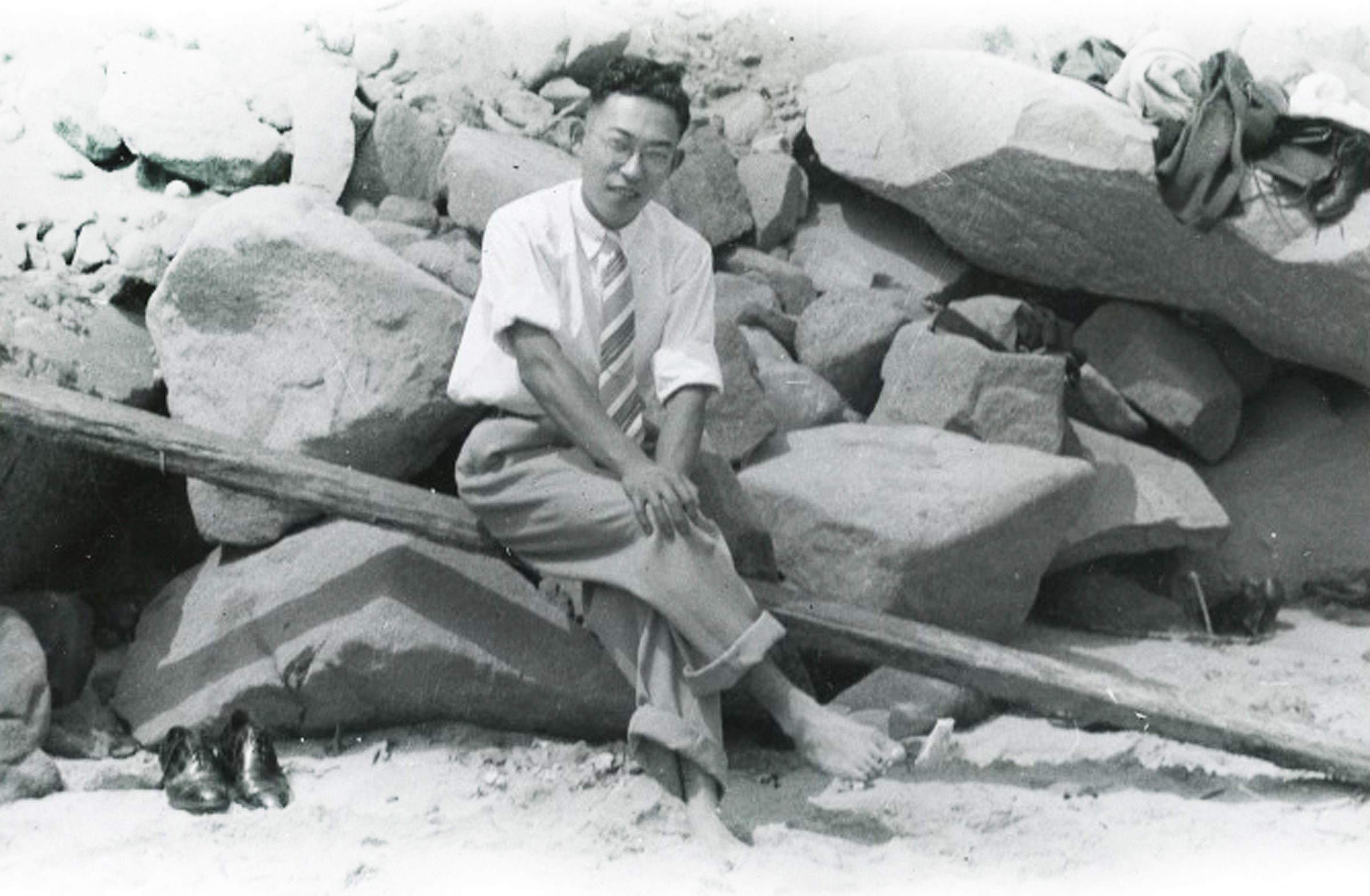

At the age of seven, James was sent to Hiroshima to live with his grandmother and uncle. He spent five years living with his relatives until his family arrived in Japan in 1929-30. Numata remained in Japan with his family for another five years to complete his education. In October of 1935, at the age of 18, Numata returned to the United States without his family (fig. 3). Existing photographs of Numata during the next ten years consist mostly of school portraits (fig. 4). Throughout his years in Japan, Numata represented his family’s experiences and surroundings with his camera (fig. 5-6). [5]

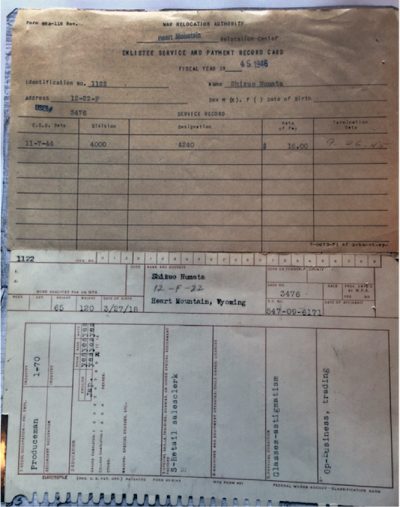

At some point in 1939-1940, Numata returned to Japan to visit his family and friends. It was during this period when James married his first wife Shizue Kajiyama.

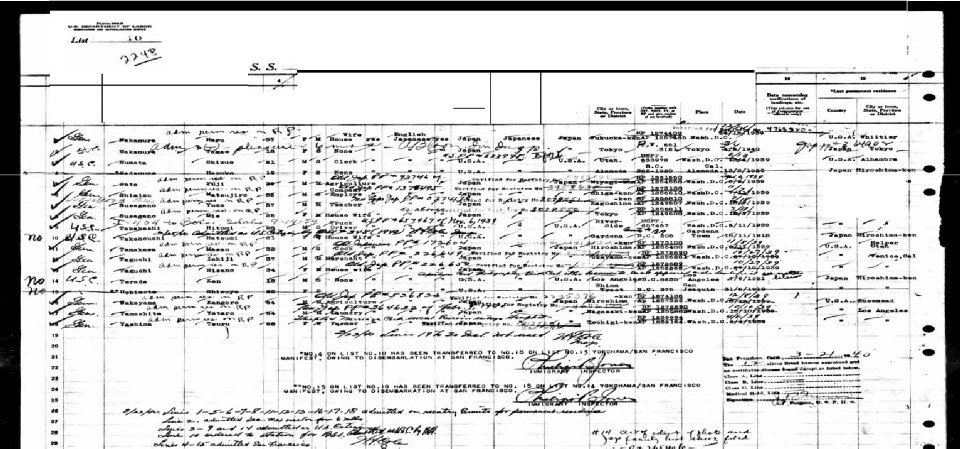

Details of Numata’s travels during this time are vague, however, California Passenger and Crew Lists reveal that Numata did return from Hiroshima to Los Angeles in March of 1940 (fig. 8). Numata would spend the next two years living in Los Angeles County with Shizue until their incarceration in 1942 (fig. 9).

• b. March 27, 1918 in Devil’s Slide, Utah to Shuichi and Hamano Numata

• 1925-1935, Lives in Hiroshima with family

• Returns to U.S. on October 26, 1935 traveling from Kobe, Japan to Los Angeles, CA

• Moves to Alhambra, California in 1935.

• Returns to Japan 1939-1940 and marries Shizue Kajiyama (b. March 5, 1919 in California)

• Lives at 948 ¾ Crocker St. Los Angeles, CA immediately before incarceration

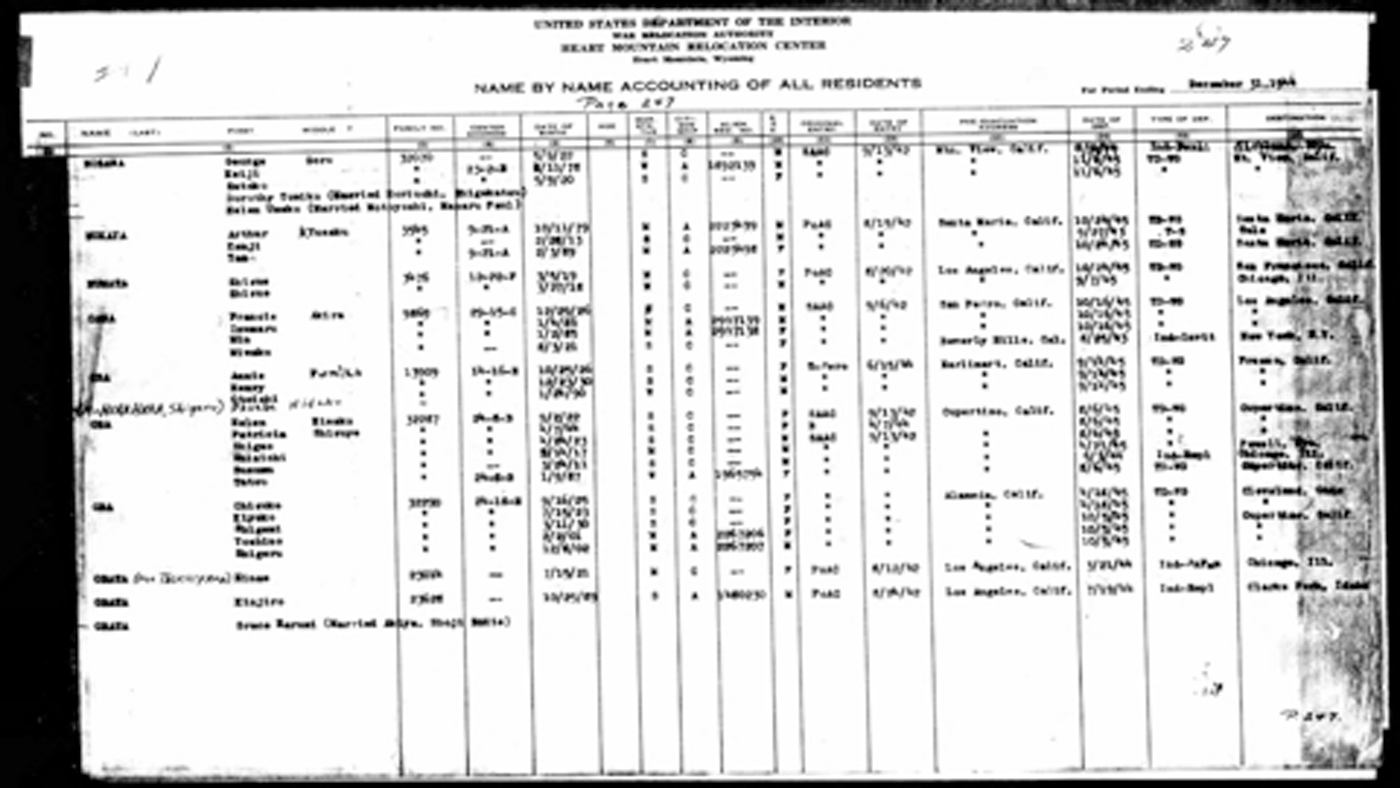

• Incarcerated at Heart Mountain, WY with his first wife on August 20, 1942.

• Leave Clearance Hearings

● March 3, 1943 fills out Application for Leave Clearance and answers “no” to questions 27 and 28.

● June [is there a day?] 1943 cancelled request for expatriation made at registration and changes answer to question 28 from no to yes

● September 2, 1943 Leave Clearance Hearing

● December 17, 1943 Shizue Kajiyama Numata (wife) leave clearance hearing

● Memo dated Jan 13, 1944 Leave Clearance Denied (Shizuo Numata)

● Feb. 11, 1944 Rehearing with wife

● May 8, 1944 Shizuo Numata leave clearance denied

● May 22, 1944 Shizue Numata (wife) given clearance

● June, 1944? JN cancels request for expatriation made at the time of registration (dates from letter to Guy Robertson, Project Director Heart Mountain from Shizuo Jim Numata dated Sept. 1, 1944, Heart Mountain)

● Sept. 1, 1944, Numata writes letter to Guy Robertson, Project Director of Heart Mountain expressing desire to change his answers from no no to yes yes and requests a rehearing.

● Sept. 8, 1944, Numata changes his answers to Yes Yes.

● Sept. 8 and 11, 1944 rehearing. Leave Clearance Board approves leave clearance.

● Sept. 19, 1944 Guy Robertson write to Dillon Myer with a recommendation to deny leave clearance

● Given leave clearance Oct. 26, 1944, by WRA, DC

● Denied leave clearance Feb. 15, 1945 by Robertson, Project Director ?

• Departs from Heart Mountain on Sept. 7, 1945, for Chicago; wife Shizue is reported to have departed roughly one month later on Oct. 24, 1945 for San Francisco.

• Marries Mary Chiyoko Muramoto on Sept. 24, 1950 at the Buddhist Church in Chicago

• 1966: Home Address 4408 N. Sheridan AR 1-4340

• 1989: Attends Heart Mountain Reunion, home address 6110 N. Kenmore Ave 60660

• 1997: Dies on September 24, 1997 at the age of 79

• James and Mary Numata Archive in the JASC Legacy Center, Chicago (10,000 images)

Numata in Heart Mountain:

Cameras and Leave Clearance

Two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 creating the legal mechanism to incarcerate West Coast Japanese Americans en masse without regard for due process or citizenship rights. Despite his birthright citizenship, James Numata was one of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans held behind barbed wire in remote concentration camps during the war (fig. 10). [6] The War Relocation Authority (the civilian agency constituted to run the camps) created case files for each incarcerated adult, which are now archived in the Washington D.C. branch of the National Archives. Numata’s case file reveals a young man, American by birth and educated in Japan, who challenged the unjust terms of his imprisonment and voiced his dissatisfaction to camp authorities.

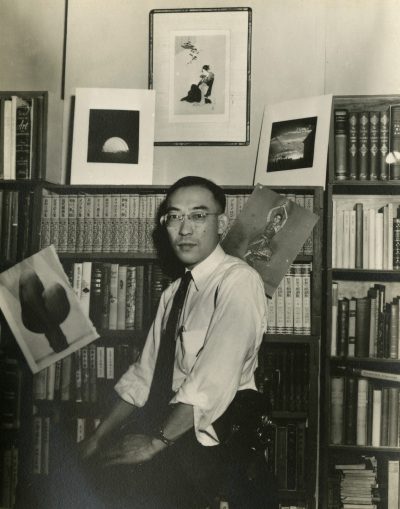

Photographs of Numata during his time at Heart Mountain are few and far between. Initially, cameras were rarely in the hands of Japanese Americans in concentration camps because the military had classified cameras as contraband—in the same category as guns, bombs, and ammunition—and Japanese Americans were forbidden from bringing cameras into camp (fig. 11). But when the War Relocation Authority took over the administration of the incarceration from the military, there was a shift in ideology and a change in the way that photography was put to use. The WRA hired photographers, including well known documentarians like Dorothea Lange in an effort to portray the incarceration process as orderly and humane. While Lange, herself, was highly critical of the incarceration and produced photographs embedded with critique, other WRA photographers created an image of Japanese Americans as complicit and the government as benign. [7]

https://cdm16786.contentdm.oclc.org/

cdm/ref/ collection/pioneerlife/id/15215

As part of this more benevolent approach, WRA officials argued successfully that cameras should be returned to Nisei living in camps outside of the Western Defense Command. Because most Japanese Americans were in camps located within the Western Defense Command, they had limited access to photography while they were incarcerated. Unlike their counterparts in West Coast camps, Nisei in Heart Mountain were eventually allowed to request that their cameras be returned to them. [8] The Heart Mountain Sentinel stated on page eight of its April 3, 1943 issue that “Applications for Cameras [were being] Accepted” (fig. 12). This meant that if James Numata had placed a camera in storage, he would have been able to file a request to have it sent to him.

A couple of pages in one of Numata’s personal photo albums archived in the JASC provide a glimpse into camp life (fig. 15). One image shows Numata posing formally with other members of the Buddhist Sunday School faculty, dated February 1945. And there are some more informal portraits of an unidentified couple accompanied by their young daughter smiling with a row of barracks and the iconic flat top of Heart Mountain framed behind them. The informally posed portraits included in Numata’s album suggest that he may have gained access, if limited, to a camera.

Other than the photograph depicting Numata’s involvement with the Buddhist Church, there is not much in Numata’s own archival collection that sheds light on his time imprisoned. But Numata’s “evacuee case file” in the National Archives reveals his deep frustration as he tried to negotiate a pathway out of Heart Mountain, which was stymied by a series of failed leave clearance hearings (fig. 16-17).

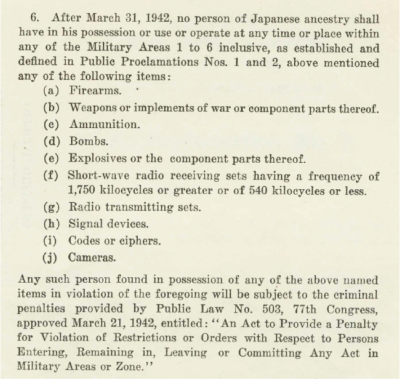

Beginning in early February of 1943, the WRA and the military began a joint effort, with different motives, to ascertain loyalty. The WRA wanted to set up a process to move Japanese Americans permanently out of camp, and the military had decided to create an all-Nisei, volunteer battalion. [9] The WRA was under pressure by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (also known as the Dies committee), which placed the WRA under investigation, not for their mistreatment of their wards, but for their alleged permissiveness. Complaints included the furnishing of whiskey and butter to the incarcerated and the release of those whose loyalty had not been adequately tested. [10] A California Senator introduced a resolution, adopted in July 1943, demanding that the President force the WRA to ascertain loyalty and segregate disloyal Japanese Americans, and that the WRA account for its resettlement plans. [11] A joint statement by the War Department and the WRA addressed the requirements of Senate Resolution 166, informing lawmakers that the WRA’s job was to “help the loyal American citizens and the law-abiding aliens in resettling outside the relocation centers….and establish residence in a normal American community,” reassuring the lawmakers that before their release “the evacuee’s background and record of behavior are carefully checked.” [12] In fact, the resolution was largely moot, as the WRA and War Department had already started a segregation process, which became known as “registration,” designed to parse loyalty. [13]

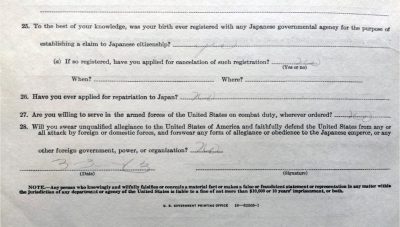

In cooperation with the military, the WRA’s mechanism for ascertaining loyalty was a lengthy form called the “Application for Leave Clearance,” given to everyone 17 and older. [14] Two questions in particular, numbers 27 and 28, were thought to reveal national allegiance (fig. 18). They asked if the respondent would serve in the US armed forces and would forswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor, placing Japanese Americans in an abominable bind. US immigration law forbade Issei (first-generation Japanese Americans) from becoming naturalized US citizens. So to forswear allegiance to Japan left them stateless. [15] For Nisei, the majority of whom had neither been to Japan nor spoke Japanese, forswearing allegiance seemed like forcing an admittal of a prior allegiance that had never existed. For some, promising to serve in the US armed forces, when their civil rights had been stripped, seemed unjust and possibly coercive. The thousands who answered “no” were branded disloyal and many were forced to move from their current camps to Tule Lake in Northern California, which the WRA designated to house “disloyal” Japanese Americans, segregated from their “loyal” counterparts. [16]

Numata’s “Evacuee Case File” reveals that he initially used the Leave Clearance Questionnaire to protest the suspension of his rights. Dated March 3, 1943, Numata’s “Application for Leave Clearance” is replete with negation. Question seven asked about desired employment to which Numata penciled in a large “No.” His compulsion to answer in the negative even overrides the format of the form itself. Instead of placing a check above either “yes” or “no,” Numata wrote out a second large “No” when asked if he was willing to be employed anywhere in the US. Under hobbies and foreign investments he responded “None.” He is more forthcoming about his proficiency in the Japanese language and in answering what magazines he reads, offering up titles including Popular Science and the Rafu Shimpo. The last three questions cut to the chase. Numata affirms that his birth had been registered for the purpose of making a claim to Japanese citizenship and that he had neither canceled that registration nor filed for repatriation. The final two questions, 27 and 28, conclude the application with two more resounding “Nos.” Numata answered “no” to both of the key questions concerning willingness to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty and to forswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor.

But, as his case file reveals, it was not his first set of “nos” to those questions. Just over a week before he filled out the full Application for Leave Clearance, Numata had signed a statement confirming his “desire to be expatriated.” [17] At the top of this document questions 27 and 28 are typed out and presented in opposite order, and Numata answers in pencil “no” to both. Stapled to this page underneath the responses, dated February 23, 1943, is the following signed statement from Numata: “It is not my desire to register with the War Relocation Authority in accordance with instructions for compulsory registration of all residents in Relocation centers as it is my desire to be expatriated.” Numata was not alone in rejecting the terms of the registration process, others refused to respond at all and far fewer volunteered for the draft than the military expected. According to historian Eric Muller, “by any measure, the registration program was a disaster.” [18]

For Numata, there is a curious discrepancy regarding desired citizenship between the signed statement and the full application, which might be explained by his attention to semantics. Numata wishes for “expatriation,” the process that would apply to a citizen of the United States who assumes citizenship in another country. According to Merriam-Webster expatriation means “removal or withdrawal from one’s native land.” But question 26 of the Application for Leave Clearance uses the term “repatriation” which means “to restore or return to the country of origin, allegiance, or citizenship.” This language assumes that only Issei, first generation Japanese Americans who were born in Japan and barred from naturalization by US law, would desire Japanese citizenship. For Numata, a Nisei and a US citizen by birth, he could only be expatriated to Japan, not repatriated. The Heart Mountain project director rejected Numata for leave with “not recommended” hand-written and underlined alongside the note “‘no’ reply to allegiance question.”

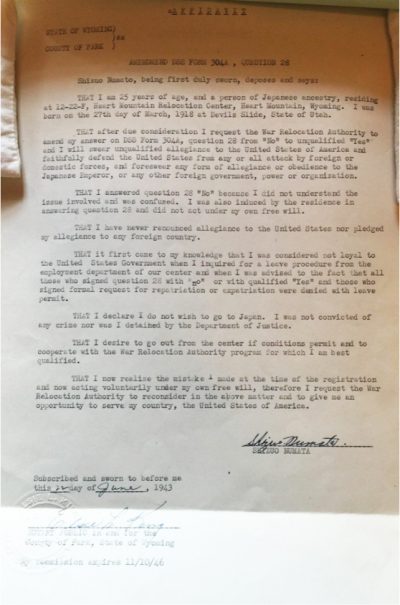

By June, Numata had changed his mind and filed an affidavit to amend his previous response and change the “nos” to “yeses” (fig. 19). Numata explained that he realized that he was perceived as disloyal to the United States after he was asked about leave procedure and had been told that those who answered “no” to question 28 or had signed a repatriation request would not be extended permits for leave. [19] The Leave Clearance Hearing Board in Heart Mountain conducted a further investigation and decided to deny leave clearance to Numata. The transcription of the hearing from September 2, 1943 reveals that while he canceled his request for “repatriation,” Numata also expressed the desire of his wife to return to Japan and his desire to accompany her “As soon as possible.”

Five months later, on February 11, 1944, Numata was given a rehearing along with his wife present to clarify their intentions. At that time, both agreed that their plan was to return to Japan after the war. At the bottom of the hearing transcription, Assistant Project Director M.O. Anderson gave the following assessment of Numata, “He is slight in stature, Japanesey in appearance and manner, and the impression gained is that he has not adjusted to American ways and retains and prefers the Japanese culture.” In addition to the racist tone of the written assessment, a form that summarized the hearing also reveals that camp officials did not see Numata as a full-fledged American citizen because they checked both the U.S. and Japan boxes for citizenship. A few days later, the Heart Mountain Project Director Guy Robertson again denied Numata’s Leave Clearance in letters both to the head of the WRA and to Numata himself. Additional correspondence in April gave the following justification: “There is reasonable ground to believe that the issuance of leave would interfere with the war program or otherwise endanger the public peace and security.” [20] His wife Shizue, however, was granted Leave Clearance on May 22nd.

In a letter to the Project Director dated September 1, 1944, Numata requested a rehearing again expressing the desire to change his answers, as well as noting a change of heart:

“My wife’s brother, Art K. Kajiyama enlisted in the armed forces from the outside in April, 1941 and we both want to remain loyal to him and what he is doing. We do not know exactly how to express ourselves or to explain what has happened but we now know that we sincerely feel less bitter about the evacuation or whatever it was that caused us to feel as we did. We feel that it is not best for people to continue to live in a Center and we would both like to get a new start as soon as possible.” [21]

Numata requested another rehearing for his leave clearance, which was held over two sessions on September 8 and 11, 1944 (fig. 20-21). During this hearing, Claud Gilmore, Assistant Relocation Program Officer, did not pull any punches and accused Numata of changing his answers not because he had discovered a greater sense of patriotism to the United States but because his draft status changed once he turned 26 and “repatriation” to Japan seemed less appealing given the likelihood of their defeat. Numata conceded that those were, in fact, the real reasons for changing his mind, and the hearing concluded.

Two days later, the Leave Clearance Hearing Board decided to grant Numata Leave Clearance citing that his release would not “constitute a threat to the internal security of the United States.” It is unclear what caused this change but Guy Robertson, the Heart Mountain Project Director, disagreed with the other members of the board and wrote to Dillon Myer, the head of the WRA, expressing his concern and requesting that Numata’s leave clearance be denied (fig. 22). On October 26, 1944 a teletype message from the WRA headquarters in Washington confirmed that the Director approved Shizuo Numata’s leave clearance. Close to a year later, on September 7, 1945 Numata departed Heart Mountain for Chicago. His wife Shizue departed roughly one month later on October 24, 1945, reportedly for San Francisco. The archival records do not reveal why there was such a lag between leave clearance and their departures and why they left separately for two different locations (fig 23). But the split became permanent and James Numata started a new life, alone in Chicago, just two months before the Heart Mountain concentration camp was closed for good. [22]

Resettlement: Numata in Chicago

_Guidebook1.81_a.jpg.

Coming out of an experience of war in which families had been torn apart, their constitutional rights had been violated, and Japanese Americans had been conflated in the popular press with the enemy, how was photography a way that Japanese Americans created a sense of home, belonging, and familial stability? As Norman Mineta put it: “Did we, in fact, have a future in America? And after all that had happened to us, to society, to the world, could we return to the places we considered home?” [23] After Numata made Chicago home, he began to make a wide range of photographs from portraits and community events to cityscapes that demonstrate the significance that photographs play in everyday acts of self-representation. Through the vernacular photograph Numata reclaimed a piece of the rights of citizenship that had been stripped from him during the war.

What brought Numata to Chicago, Illinois? Japanese Americans were mostly forbidden from returning to their West Coast homes until January 1945. While returning to Los Angeles was a possibility in 1945, it may well be that Numata wanted to start anew far from his wife and the geography that had anchored their lives together just prior to the war. The War Relocation Authority was charged not just with administering the camps, the federal agency was also tasked with coming up with a plan for the resettlement of Japanese Americans as they obtained leave clearance. Working to “scatter Japanese Americans as much as possible and encourage them to lose strong ethnic ties,” the WRA played a significant factor in the development of newer Japanese American communities, like the one in Chicago. [24] According to historian Greg Robinson, “the case of the Japanese Americans demonstrates the persistence of the dubious belief that destruction of ethnic communities will ensure assimilation and social harmony.” [25] Dispersal was seen as a solution to preventing ethnic enclaves, and in doing so creating a situation in which Japanese Americans were forced to assimilate with different ethnicities. [26]

The WRA set up its first resettlement office in Chicago. According to a Chicago area resettlement official, the goal was “the complete incorporation or absorption into our every community social activity where only the difference in physical features are noticeable.” A letter from the supervisor of the Chicago relocation office to the head of the employment division for the WRA, explained the chief barrier to such a goal: “If it were not for the housing situation which remains acute in Chicago and probably always will, we should be tempted to expand this program very much. The jobs are here and we know we can place most people within a short time after their arrival but the housing facilities are so limited, we must move rather more slowly than we would like.” [27] Housing continued to be a central obstacle to Japanese Americans newly arriving in Chicago. In addition to housing, the WRA relocation office supervisor complained of police arrests for the possession of items that had been contraband in camp, including radios and cameras, and “other somewhat petty reasons” as another barrier for Japanese Americans. [28]

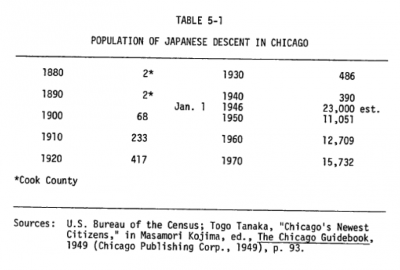

Arriving alone in the Fall of 1945 Numata became just one of the roughly 20,000 Japanese Americans who relocated to Chicago during the war. With a meager population of fewer than 400 before World War II, Japanese Americans had not been well represented in the Chicago area (fig. 24). [29] The wave of Japanese Americans directed to resettle in Chicago by the WRA encountered a highly segregated city with a growing demand in industrial jobs, but race-based restrictions barring them from skilled jobs and housing.

World War II led to an uptick in black employment in industrial centers such as Chicago, but the labor opportunities for African-American workers were limited in comparison to their white counterparts. Excluded from most skilled labor positions, African Americans worked in unskilled positions in Chicago’s factories. While they made up a large number of the workforce, very few (if any at all) held managerial positions. Similarly, the housing market in Chicago was extremely segregated. Racist housing practices were already well entrenched at the time, and black Chicagoans were more often than not forced into less developed neighborhoods, concentrating poverty and limiting access to resources. As the Japanese American population of Chicago grew during the mid 1940s, these new Chicagoans occupied what historian Charlotte Brooks terms the “in-between position in the city’s racial hierarchy.” [30]

Overall, the combination of racist housing market practices, and WRA regulation deterred any true Japanese American neighborhood from developing. The most prominent areas of Japanese American resettlement occurred in the Near North Side, at the intersection of Division and Clarke, as well as the “Oakland/Kenwood and Woodlawn areas of Hyde Park near the University of Chicago” (fig. 25-28). [31] However, this did not prevent the development of a vibrant Japanese American community in postwar Chicago.

This “in-between” position greatly influenced how the Japanese American community developed in Chicago during the 1940s. For the most part, Japanese Americans were more widely accepted as coworkers and neighbors by both black and white Chicagoans. As fellow minorities, many African Americans saw Japanese Chicagoans as allies in their fight for civil rights. Cooperation between black and Japanese American organizations was not at all uncommon at this time, and represents an alliance created to combat discriminatory practices in housing and the workplace. [32]

wp-content/uploads/2014/07/

1999.002_Guidebook1.79_a.jpg

As “alternatives” to African Americans, whites saw Japanese Americans as “model” citizens and coworkers. This gave Japanese Americans access to some advantages not available to Chicago’s black population, particularly in the workforce. While somewhat limited, the new Japanese American migrants mostly succeeded at finding work in Chicago. From factory worker to chick-sexer, employment opportunities were generally available (fig. 29-30). Again, the “in-between” status allowed them certain advantages not readily available to black workers in Chicago. White workers oftentimes saw them as better coworkers than African Americans, and embraced them as “model” examples of how minorities should act, which, at times, led to tension between Japanese American and black workers. [33]

Numata photographed many businesses and people at work as part of his contribution to the Chicago Japanese American Year Book including Image 4.5: Chick sexers, ca. 1949, which depicts a group of Japanese American chick sexers at work. According to scholar and archivist Ryan Yokota, “Chick sexing entails the differentiation of male versus female chicks in the immediate days after being hatched, in order to cull the male chicks and preserve the female chicks. Since female chicks were desired because they could lay eggs, chick sexing could help to guarantee for egg producers that their feed would only be used for egg-laying hens instead of being wasted on non-egg-producing cockerels.”

The photograph itself shows three Japanese-American men posing while others continue to work. Men’s hands are blurred as they sort the newly born chicks into boxes based on the chicks’ sex. Each worker has his own station, lit by an overhead light. They work side by side in what appears to be a relatively small space. Included in the 1949 Chicago Guidebook for Japanese Americans, the photograph was part of an ad used by the National Chick Sexing Association to promote chick sexing as an employment opportunity for recently relocated Japanese Americans.

What does this photograph, and its purpose tell us? Chick sexing was an occupation dominated by Japanese Americans. According to Yokota, “specific methods of chick sexing had been developed in Japan as a specialized skill, and were introduced to the U.S. through the work of Japan-trained chick sexers, who helped popularize the trade.” The result of this was chick sexing schools and ads that specifically targeted Japanese Americans.

What else could this photograph tell us about Japanese Americans in Chicago during this time period? The fact that chick sexing was, for the most part, an exclusively Japanese- American occupation, could tell us something about the economic climate of Chicago during this time. Did so many Japanese Americans seek out work as chick sexers because they were barred from other professions? How was the Japanese American workforce segregated from other workforces in Chicago during this time? Did white Chicagoans not want to work with Japanese Americans? By contextualizing this photograph within the history of Chicago during the 1940s, we can question its many meanings. This photograph may be viewed as a representation of Japanese American men hard at work in an occupation that they have long been skilled at. It may also be viewed as an example of the segregation Japanese Americans faced when entering the workforce in Chicago.

See https://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2016/9/28/chick-sexers-1/ and

https://www.jasc-chicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/1999.002_Guidebook1.79_a.jpg

This type of inclusion, however, was not present in the housing market. Similar to African Americans, Japanese Americans faced housing discrimination at every turn. Landlords were unwilling to rent to Japanese Americans in certain parts of the city, and suburban housing was mostly restricted to them until well into the 1950s. [34] Due to these practices, Japanese Americans ended up living in locations throughout Chicago that for the most part had been predominantly African-American neighborhoods in the earlier decades of the twentieth century (fig. 31). Not only were Japanese American housing options restricted through racist market practices, but through government regulation.

Despite the many hurdles faced as a result of WRA policies and Chicago’s racial climate, Japanese Americans managed to create a place to call their own in this new setting. Numata’s photographs focus on the creation of clubs and other social networks that also reveal the shift in the assimilationist directives of the WRA’s “ethnic dispersal program.” Starting roughly in 1948, Numata began to photograph the lives of Japanese Americans in Chicago. From local events and gatherings (fig. 32-45), to family portraits, to business promotions Numata’s camera captured a growing and vibrant Japanese American community. This increase in Numata’s photographic activity coincided with his relationship with Mary Chiyoko Muramoto (they were married on September 24, 1950 at the Chicago Buddhist Church), whose father owned his own photography studio in Colorado (fig. 46).

Courtesy of the Mary and James Numata Photograph Collection at the Japanese American Service Committee Legacy Center in Chicago, IL.

Numata’s photographs depict the roles that community organizations, religion, and small businesses played in the creation of a cohesive community identity. Photographs of employees smiling and lined up behind a dry cleaner counter, or women posing in their beauty shop are all part of Numata’s contributions to the Chicago Japanese American Year Book, which recorded local businesses in a directory. Another image of what looks like members of a family, who are staffing the Rainbow Foods store, emphasizes shelves loaded with the postwar abundance of highly processed foods. Wonder bread, corn flakes, and Quaker oats dominate shelves along with row after row of canned goods. Poster-sized advertisements for Nescafe and cereal hang from the ceiling. The staff is lined up behind the bread shelves, and they smile directly at the camera. The store presents a stark contrast with the rations and commissary that this family would have experienced during the war (fig. 43). Although Numata himself was employed as a bookkeeper, some of his photographs, like Rainbow Foods, which were used in the Year Book, imply a side job in commercial photography. [35]

As early as 1946, a strong Japanese American community was developing in Chicago. A significant reason for this was the existence of already influential Japanese American community organizations in Chicago. The influx of Nisei from the incarceration camps only strengthened these organizations and led to increased development of various social groups such as the Shin-yu-kai (friendship club) and the All Girls Club that allowed Japanese Americans to stay connected across Chicago (fig. 47-49). Possibly the most prominent of these groups were religious organizations such as the Chicago Buddhist Church, of which Numata was a member. [36] Working with the same WRA that encouraged dispersal, Buddhist churches, and other organizations in the Chicago area tried to create a welcoming environment for the incoming Japanese Americans (fig. 50-59). [37] Of course, this would not have been as successful without a large group of Nisei determined to maintain cultural ties and practices in a new city. Social groups affiliated with church groups organized events such as carnivals, dances, and picnics for Chicago’s Japanese American community. It is here where Numata’s contribution to our understanding of Japanese American life in postwar Chicago is most significant.

The photographs show Japanese Americans in the act of creating and building community through meaningful social activity. Numata frames the aproned women of the Buddhist Church who stand behind the counter offering plates of noodles and sushi at the carnival just below center so he can include the crepe paper decorations hanging from the ceiling within his frame (fig. 50). The women themselves are lined up for the shot and some are eating noodles, snow cones, and one is drinking bottled Coca Cola. Together they assert a claim to a group identity predicated on shared cultural practices and shared beliefs. In another photograph, a group of eight Nisei/Kibei and one young white man smile broadly as they pose during the Chicago Buddhist Church picnic. It’s one of the few instances in Numata’s photographs that depicts social interaction between Japanese Americans and white Americans. Numata is crouching behind a friend with his hands on his shoulders, and Mary who would become Jim’s wife in less than a year is sitting on the other side of the blanket (fig. 51). Another photograph of a Shin-yu-kai event depicts fun at the beach. One man and woman are playing a game that has put them in intimate proximity. He passes a lifesaver from his mouth to hers as others in bathing suits and rolled-up pants look on amused (fig. 48).

Numata continued to photograph his experiences and those of his fellow Chicagoans until his death in 1997. His extensive collection depicts a variety of events throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Sprinkled throughout the Mary and James Numata Collection at the JASC are landscapes of Chicago taken by Numata all over the city. These photographs reveal an imagemaker not just interested in producing images for business directories, but a man deeply interested in photography for its aesthetic value. From striking images of Chicago’s skyline, to carefully framed shots of wildlife and landmarks, Numata reveals his attention to detail (fig. 60-65). Through these images Numata demonstrated a love for the architecture and landscape of the city of Chicago, using photography to explore light, shadow, and pattern—very much in keeping with mid-century art photography. In these cityscapes, Numata is more like a flaneur, using his camera to observe the nuances of the city and in a sense break down the invisible barriers that structural racism had erected, and that had been all too visible to Numata during his wartime confinement.

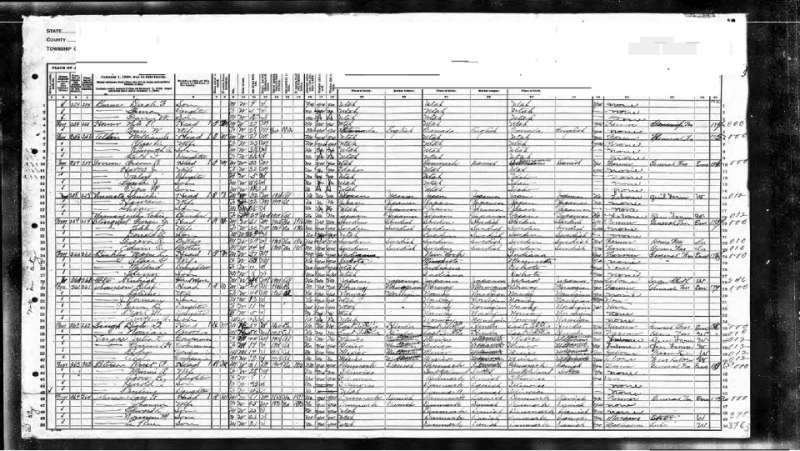

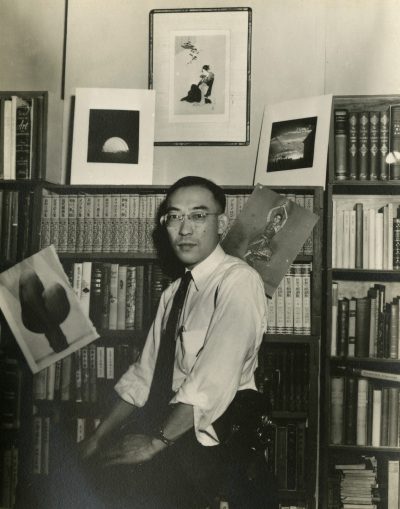

In his self-portrait, Numata reveals a desire to construct himself in this new urban space as an artist (fig. 66). Surrounded by books in Japanese and English, he sits at his desk with five images displayed around him. Framed on the wall is a Japanese print, two of Numata’s own photographs are propped against the wall on top of the bookshelf, and two other images are casually tacked onto the shelf’s wood slats. One image, which appears to be torn from a magazine, depicts a woman’s fishnet stocking clad legs, and the other, a classical Indian dancer posing with arms overhead. In addition to his Japanese patrimony placed just above his own work, he includes a nod to fashion and dance in his photographic construction of self. Perhaps most importantly, strapped at his hip, Numata brandishes his camera in the self-portrait, a nod to the painterly conceit of including palette and brush, he includes his chosen medium as he looks with a serious expression directly into the lens of the camera that is doing the actual representational work. While it may be impossible to know who laid eyes on Numata’s photographs while he was still alive, it is clear that Numata, although an amateur, fashioned himself into a committed photographer.

Conclusion: The Heart Mountain Reunion

While Numata managed to mark his time at Heart Mountain photographically, albeit sparsely, many Japanese Americans have empty pages in their family photo albums because they did not have access to cameras while they were incarcerated. Representations of rites of passage are missing. Casual snapshots were not taken. Numata’s photographs made during the decades he spent in Chicago repopulate those pages and serve multiple functions. At the time they were made, they recorded the growth of the Japanese American community and could be used instrumentally to illustrate the Chicago Japanese American Year Book, for example. But they could also be understood to serve a more symbolic function. Numata’s case file reveals how he struggled with the imposed categories of loyal and disloyal. Numata’s initial refusal to answer the Leave Clearance Application affirmatively and his request for expatriation could be read as a form of protest through negation. His photographs of Chicago, however, participate in protest via affirmation. As Lane Hirabayashi writes,

“WRA resettlement policy can be seen as a pernicious form of forced Americanization that was inherently inimical to any positive dimensions of Japanese American identity, culture, and community.” [38]

Despite the government’s desire to use relocation as a method of ethnic dispersal, Numata’s photographs depict the makings of a nascent Chicago Nihonmachi (Japantown). They are rife with the expression of Japanese American identity, culture, and community.

With increased scrutiny to the Numata collection, perhaps the photographs of a fairly unknown photographer can also play a role in “reclaiming,” in Hirabayshi’s terms, as part of a “post-Redress politics of interpretation.” [39] Hirabayashi concludes his study of WRA resettlement photographs, titled Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens, with a desire to read his own family’s story into a photograph of Issei men at a home for seniors in San Francisco. He is not directly related to those pictured but he can project his own family history into the frame. Perhaps Numata’s photographs too can give a fuller picture of postwar Japanese American life, depicted by someone who worked to build that life from within as both a participant and an observer.

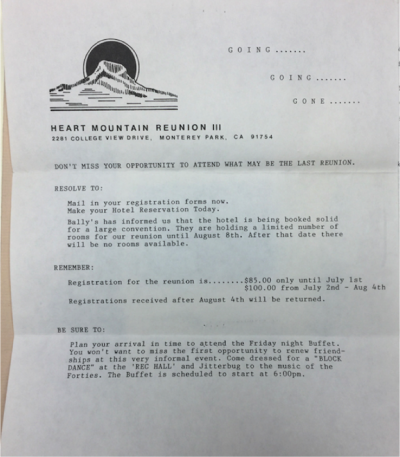

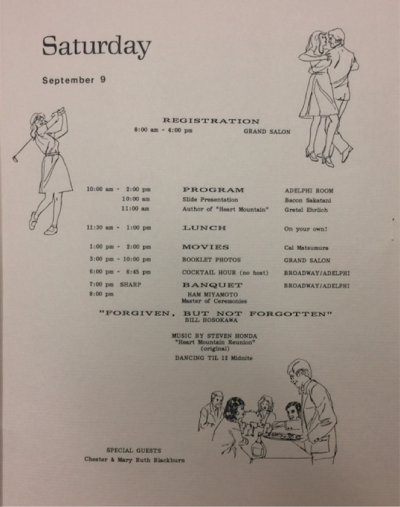

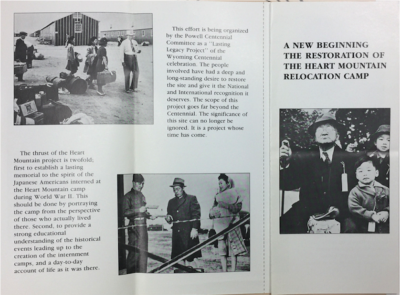

Despite the tense encounters Numata had with camp officials and the barriers he faced in leaving Heart Mountain, at the age of 71, he decided to attend a camp reunion. In 1989, Jim Numata booked a trip to Reno, Nevada. He ordered ahead for prime rib at dinner and had a ticket for the Sunday farewell brunch (fig. 67-68). The pleas from the Heart Mountain reunion committee had worked. In all caps the invitation warned, “DON’T MISS YOUR OPPORTUNITY TO ATTEND WHAT MAY BE THE LAST REUNION” (fig. 69). To lighten that morbid message, attendees were encouraged to arrive on Friday for jitterbugging at the “Rec Hall Block Dance.” [40] At Saturday’s banquet, Bill Hosokawa gave the keynote address titled “Forgiven, but not Forgotten” (fig. 70). Numata made the trip alone and held onto his Bally’s guest card, the program, and other documentation of his trip.

Judging from the list of attendees, which numbered approximately 1000, the aging Nisei likely felt a sense of nostalgia. Numata also retained documents from his trip that include a survey asking how a proposed Heart Mountain Memorial Park should be constructed, and a brochure for selling photo books of different camps called “Official Historical War Relocation Authority Photographs and Documents” by TeeCom productions (fig. 71-72). The brochure for the photo books warned of that the original photographs were deteriorating and that “In another decade all photographic records of the evacuation and internment will be but a memory.” [41] It would not have been possible to know that twenty-five years later, the extensive collection of WRA photography would be preserved and digitized, accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. But what James Numata would most certainly have known at the time was that the photographic archive that he had created over his lifetime needed a home. Ten years after his trip, and two years after Numata’s death, the Japanese American Service Committee became that home.

About the Curators:

Jasmine Alinder is Associate Dean of the Humanities and Associate Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Trained as an historian of photography, she received her PhD in Art History from the University of Michigan in 1999. Since then she has published primarily on documentary photography, including the book Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration (University of Illinois Press, 2009); the catalogue to accompany the exhibition Yasuhiro Ishimoto: Someday, Chicago (DePaul Art Museum and University of Chicago Press, 2018); and essays in Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II (ed. Eric Muller, UNC Press, 2012); in Outrage! Art, Controversy, and Society (eds. Richard Howells, Judith Schachter, and Andreea Ritivoi, Palgrave MacMillan, 2012); and in Photography and Migration (ed. Tanya Sheehan, Routledge, 2018). Alinder has also been involved with digital, public humanities projects: serving as the project director for the “March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project” (www.marchonmilwaukee.uwm.edu); as lead academic advisor and content curator for the “Orange Story” (Japanese American WWII Confinement: A Cinematic Digital History Project, www.theorangestory.org); and as a scholar for the Virtual Asian American Art Museum. With a Ryskamp fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies, she began work on a book about photography, war, and censorship in the wake of 9/11 that is now under contract with the University of North Carolina Press.

Jamison Ellis received his MS in Urban Studies from UWM in 2018. While a student he worked on multiple projects including the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, the Wisconsin Farms Oral History Project, and the Virtual Asian American Art Museum’s online exhibit Home Making: James Numata’s Photography of Postwar Chicago. His personal research and thesis, Measured Expectations: An Examination of Urban Agriculture Development and Operations in Milwaukee, WI, focused on urban agriculture and its role in community development in Milwaukee’s northwest side. In the coming years, Jamison hopes to find a way to combine his love of history and skills as a researcher to assist in community-based nonprofit work in New York City.

Endnotes

[1] James Numata’s Buddhist Prayer book, James Numata Collection, No. 63 p. 22, Murray Printing co, Cambridge MA, Box 24 1999.002, Stacks 2, 6F, Japanese American Service Committee, Chicago.

[2] Roger Daniels, “Words do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans.” In Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura, eds. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005. https://www.nps.gov/tule/learn/education/upload/RDaniels_euphemisms.pdf

[3] Raymond K. Okamura, “The American Concentration Camps: A Cover-up Through Euphemistic Terminology,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 10.3 (Fall 1982): 101.

[4] National JACL Committee, “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II,” April 27, 2013, 7.

[5] See the JASC’s online exhibition that includes Numata called “Two Countries Two Kibei”: https://www.jasc-chicago.org/legacy-center-archive-library/two-countries-two-kibei/

[6] According to Roger Daniels, “Although more than 120,000 individuals were held in relocation centers at one time or another, the camp population peaked at a little over 107,000 in the winter of 1943.” Roger Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 72.

[7] For more on photography and Japanese American incarceration see Jasmine Alinder, Moving Images: Photography and Japanese American Incarceration (Urbana, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009). Also see Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro, eds., Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

[8] For more on photography inside Heart Mountain see Eric L. Muller ed., Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

[9] Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 33. For a chronology of Japanese Americans during the war, see Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H.L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress (1986, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991), xv-xxi.

[10] “Comments by the War Relocation Authority on Newspaper Statements Attributed to Representatives of the House Committee on Un-American Activities,” Dies Committee Material, Records of the WRA, Headquarters Records, Basic Documentation and Informational Files, Nonserial Informational Issuances, WRA Publications, Dies Committee Material, Box 1, RG 210, NARA.

[11] According to Eric L. Muller, both the DIES Committee and “a Senate military affairs committee headed by Kentucky Senator Albert B. (‘Happy’) Chandler” were involved in investigations into the WRA camps. Both committees concluded that “disloyal internees at the camps should be separated, or ‘segregated,’ from the rest of the population and interned separately.” Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 26.

[12] Press release, Justice Byrnes, “A Comprehensive Statement in Response to Senate Resolution 166,” July 17, 1943. Records of the WRA, Headquarters Records, Basic Documentation and Informational Files, Nonserial Informational Issuances, WRA Publications, Dies Committee Material, Box 2, RG 210, NARA.

[13] Muller, 35.

[14] There were similar but slightly different forms for Nisei men of draft age and for Issei and Nisei women. For more on the questionnaires, see chapter five of Eric L. Muller’s American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007): 31-38.

[15] Because of the outcry, the language was changed but that did little to alleviate Issei anxiety, Muller, 35-36.

[16] According to Roger Daniels, “6,700 of the 75,000 respondents” answered “no” to one or both of the key loyalty questions. See Daniels, “The Forced Migrations,” 74. Also see Daniels, et al., “Chronology,” xx. According to Muller, 22% of Nisei men answered “no” to question 28. Muller, 38.

[17] Signed statement by Shizuo Numata, February 23, 1943 to War Relocation Authority, Washington DC, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[18] Muller, 35.

[19] The actual determination process or methodology for used to decide loyalty cases changed at different points of the process and the WRA developed different criteria than the military and joint board. For more on the complexities of the screening process see Muller, 39-106.

[20] “Notice of Action on Application for Leave Clearance,” to Shizuo Numata from Guy Robertson, April 27, 1944, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[21] Shizuo Numata to Guy Robertson, September 1, 1944, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[22] For more about Heart Mountain see the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center website, https://www.heartmountain.org/history.html

[23] Norman Mineta, “Forward,” Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA’s Photographic Section, 1943-1945 by Lane Ryo Hirabayashi with Kenichiro Shimada (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press, 2009), xiv.

[24] Michael Daniel Albert, “Japanese American Communities in Chicago and the Twin Cities,” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1980), 114-115.

[25] Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012), 30.

[26] Charlotte Brooks, “In the Twilight Zone between Black and White: Japanese American Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1945,” The Journal of American History 86, no. 4 (2000): 1667.

[27] Letter to Mr. TW Holland, Chief, Employment Division WRA from Elmer Shirrell, Relocation Supervisor, Relocation Office Chicago, May 25, 1943, RG 210 Records of the WRA, Washington Office Records, Chron File, Relocation Offices, Chicago, Illinois May 1943-Jan 1944 (Entry 21) BOX 11, Folder: Relocation Office (Chicago, IL) May 1943, NARA.

[28] Letter to Thomas W. Holland, from Elmer Shirrell Folder, July 24, 1943, Relocation Office (Chicago, IL) June-July 1943 RG210 Records of the WRA, Washington Office Records, Chron File, Relocation Offices, Chicago, Illinois May 1943-Jan 1944 (Entry 21) BOX 11, NARA.

[29] Albert, 89-90.

[30] Brooks, “In the Twilight Zone,” 1656.

[31] Matthew M. Briones, Jim and Jap Crow: A Cultural History of 1940s Interracial America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 163.

[32] Briones, Jim and Jap Crow, 179.

[33] Alan Jacobson and Lee Rainwater, “A Study of Management Representative Evaluations of Nisei Workers,” Social Forces 32, no. 1 (1953).

[34] Briones, Jim and Jap Crow, 153.

[35] See “Two Countries Two Kibei.”

[36] Founded in 1944, The Chicago Buddhist Church was just one of many Buddhist establishments that adopted the descriptor of “church” during the first half of the 20th century. That same year the Buddhist Mission of North America changed its name to the Buddhist Churches of America in 1944 as a result of decisions made by Buddhists held in the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. According to Paul David Numrich, one of the first instances of this shift was in 1905 when the San Francisco [mission] changed its name to the Buddhist Church of San Francisco. While Numrich spends little time questioning whether or not this shift from temple to church was “an attempt to fit in with American sensibilities and public sentiment of the time,” it is important to note this shift in relation to Japanese American incarceration and resettlement. See Paul David Numrich ed., North American Buddhists in Social Context (Boston, MA: Brill, 2008), 95, 104.

[37] Albert, 217.

[38] Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens (Boulder: Univ of Colorado Press, 2009), 6.

[39] Hirabayashi, 193-5.

[40] Numata Collection, JASC, Folder: Heart Mtn Reunion Material, 1989—Reno, NV 24.12, Box 24 1999.002

[41] Stone Ishimaru, Poston I, WWII US Army Signal Corp photographer in the Pacific theater.

Bibliography

Albert, Michael Daniel. “Japanese American Communities in Chicago and the Twin Cities.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1980.

Alinder, Jasmine. Moving Images: Photography and Japanese American Incarceration. Urbana, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Briones, Matthew M. Jim and Jap Crow: A Cultural History of 1940s Interracial America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Brooks, Charlotte. “In the Twilight Zone between Black and White: Japanese American Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1945.” The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4 (Mar. 2000): 1655-1687.

Daniels, Roger. Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans and World War II. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

Daniels, Roger. “Words do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans.” In Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century, edited by Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura, 183-207. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Daniels, Roger, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H.L. Kitano, eds. Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991.

Gordon, Linda and Gary Y. Okihiro, eds. Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. New York: WW Norton, 2008.

Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. “History – Life in Camp.” Accessed Feb. 20, 2018. https://www.heartmountain.org/history.html.

Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo. Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press, 2009.

National JACL Committee, “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II,” April 27, 2013.

Jacobson, Alan, and Lee Rainwater. “A Study of Management Representative Evaluations of Nisei Workers.” Social Forces, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Oct. 1953): 35-41.

JASC. “Two Countries / Two Kibei.” Accessed Feb. 20, 2018. https://www.jasc-chicago.org/legacy-%20center-archive-%20library/two-countries-%20two-%20kibei/.

Muller, Eric L. American Inquisition. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Muller, Eric L. Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Numrich, Paul David, ed. North American Buddhists in Social Context. Boston: Brill, 2008.

Okamura, Raymond K. “The American Concentration Camps: A Cover-up Through Euphemistic Terminology,” Journal of Ethnic Studies, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Fall 1982).

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012.

Archives

Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/

Mary and James Numata Photograph Collection, Legacy Center Archives, Japanese American Service Committee, Chicago.

War Relocation Authority records. Record Group 210. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

[1] James Numata’s Buddhist Prayer book, James Numata Collection, No. 63 p. 22, Murray Printing co, Cambridge MA, Box 24 1999.002, Stacks 2, 6F, Japanese American Services Committee, Chicago.

[2] See the JASC’s online exhibition that includes Numata called “Two Countries Two Kibei”: http://www.jasc-chicago.org/legacy-center-archive-library/two-countries-two-kibei/

[3] According to Roger Daniels, “Although more than 120,000 individuals were held in relocation centers at one time or another, the camp population peaked at a little over 107,000 in the winter of 1943.” Roger Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 72.

[4] For more on photography and Japanese American incarceration see Jasmine Alinder, Moving Images: Photography and Japanese American Incarceration (Urbana, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009). Also see Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro, eds., Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

[5] For more on photography inside Heart Mountain see Eric L. Muller ed., Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

[6] Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 33. For a chronology of Japanese Americans during the war, see Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H.L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress (1986, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991), xv-xxi.

[7] “Comments by the War Relocation Authority on Newspaper Statements Attributed to Representatives of the House Committee on Un-American Activities,” Dies Committee Material, Records of the WRA, Headquarters Records, Basic Documentation and Informational Files, Nonserial Informational Issuances, WRA Publications, Dies Committee Material, Box 1, RG 210, NARA.

[8] According to Eric L. Muller, both the DIES Committee and “a Senate military affairs committee headed by Kentucky Senator Albert B. (‘Happy’) Chandler” were involved in investigations into the WRA camps. Both committees concluded that “disloyal internees at the camps should be separated, or ‘segregated,’ from the rest of the population and interned separately.” Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 26.

[9] Press release, Justice Byrnes, “A Comprehensive Statement in Response to Senate Resolution 166,” July 17, 1943. Records of the WRA, Headquarters Records, Basic Documentation and Informational Files, Nonserial Informational Issuances, WRA Publications, Dies Committee Material, Box 2, RG 210, NARA.

[10] Muller, 35.

[11] There were similar but slightly different forms for Nisei men of draft age and for Issei and Nisei women. For more on the questionnaires, see chapter five of Eric L. Muller’s American Inquisition (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2007): 31-38.

[12] Because of the outcry, the language was changed but that did little to alleviate Issei anxiety, Muller, 35-36.

[13] According to Roger Daniels, “6,700 of the 75,000 respondents” answered “no” to one or both of the key loyalty questions. See Daniels, “The Forced Migrations,” 74. Also see Daniels, et al., “Chronology,” xx. According to Muller, 22% of Nisei men answered “no” to question 28. Muller, 38.

[14] Signed statement by Shizuo Numata, February 23, 1943 to War Relocation Authority, Washington DC, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[15] Muller, 35.

[16] The actual determination process or methodology for used to decide loyalty cases changed at different points of the process and the WRA developed different criteria than the military and joint board. For more on the complexities of the screening process see Muller, 39-106.

[17] “Notice of Action on Application for Leave Clearance,” to Shizuo Numata from Guy Robertson, April 27, 1944, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[18] Shizuo Numata to Guy Robertson, September 1, 1944, Numata Evacuee Case File, NARA.

[19] For more about Heart Mountain see the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center website, http://www.heartmountain.org/history.html

[20] Norman Mineta, “Forward,” Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA’s Photographic Section, 1943-1945 by Lane Ryo Hirabayashi with Kenichiro Shimada (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press, 2009), xiv.

[21] Michael Daniel Albert, “Japanese American Communities in Chicago and the Twin Cities,” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1980), 114-115.

[22] Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012), 30.

[23] Charlotte Brooks, “In the Twilight Zone between Black and White: Japanese American Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1945,” The Journal of American History 86, no. 4 (2000): 1667.

[24] Letter to Mr. TW Holland, Chief, Employment Division WRA from Elmer Shirrell, Relocation Supervisor, Relocation Office Chicago, May 25, 1943, RG 210 Records of the WRA, Washington Office Records, Chron File, Relocation Offices, Chicago, Illinois May 1943-Jan 1944 (Entry 21) BOX 11, Folder: Relocation Office (Chicago, IL) May 1943.

[25] Letter to Thomas W. Holland, from Elmer Shirrell Folder, July 24, 1943, Relocation Office (Chicago, IL) June-July 1943 RG210 Records of the WRA, Washington Office Records, Chron File, Relocation Offices, Chicago, Illinois May 1943-Jan 1944 (Entry 21) BOX 11, NARA.

[26] Albert, 89-90.

[27] Brooks, “In the Twilight Zone,” 1656.

[28] Matthew M. Briones, Jim and Jap Crow: A Cultural History of 1940s Interracial America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 163.

[29] Briones, Jim and Jap Crow, 179.

[30] Alan Jacobson and Lee Rainwater, “A Study of Management Representative Evaluations of Nisei Workers,” Social Forces 32, no. 1 (1953).

[31] Briones, Jim and Jap Crow, 153.

[32] See “Two Countries Two Kibei.”

[33] Founded in 1944, The Chicago Buddhist Church was just one of many Buddhist establishments that adopted the descriptor of “church” during the first half of the 20th century. That same year the Buddhist Mission of North America changed its name to the Buddhist Churches of America in 1944 as a result of decisions made by Buddhists held in the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah. According to Paul David Numrich, one of the first instances of this shift was in 1905 when the San Francisco [mission] changed its name to the Buddhist Church of San Francisco. While Numrich spends little time questioning whether or not this shift from temple to church was “an attempt to fit in with American sensibilities and public sentiment of the time,” it is important to note this shift in relation to Japanese American incarceration and resettlement. See Paul David Numrich ed., North American Buddhists in Social Context (Boston, MA: Brill, 2008), 95, 104.

[34] Albert, 217.

[35] Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens (Boulder: Univ of Colorado Press, 2009), 6.

[36] Hirabayashi, 193-5.

[37] Numata Collection, JASC, Folder: Heart Mtn Reunion Material, 1989—Reno, NV 24.12, Box 24 1999.002

[38] Stone Ishimaru, Poston I, WWII US Army Signal Corp photographer in the Pacific theater.

[39] Roger Daniels, “Words do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans.” In Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura, eds. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005. https://www.nps.gov/tule/learn/education/upload/RDaniels_euphemisms.pdf

[40] Raymond K. Okamura, “The American Concentration Camps: A Cover-up Through Euphemistic Terminology,” <em>Journal of Ethnic Studies</em> 10.3 (Fall 1982): 101.

[41] National JACL Committee, “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II,” April 27, 2013, 7.