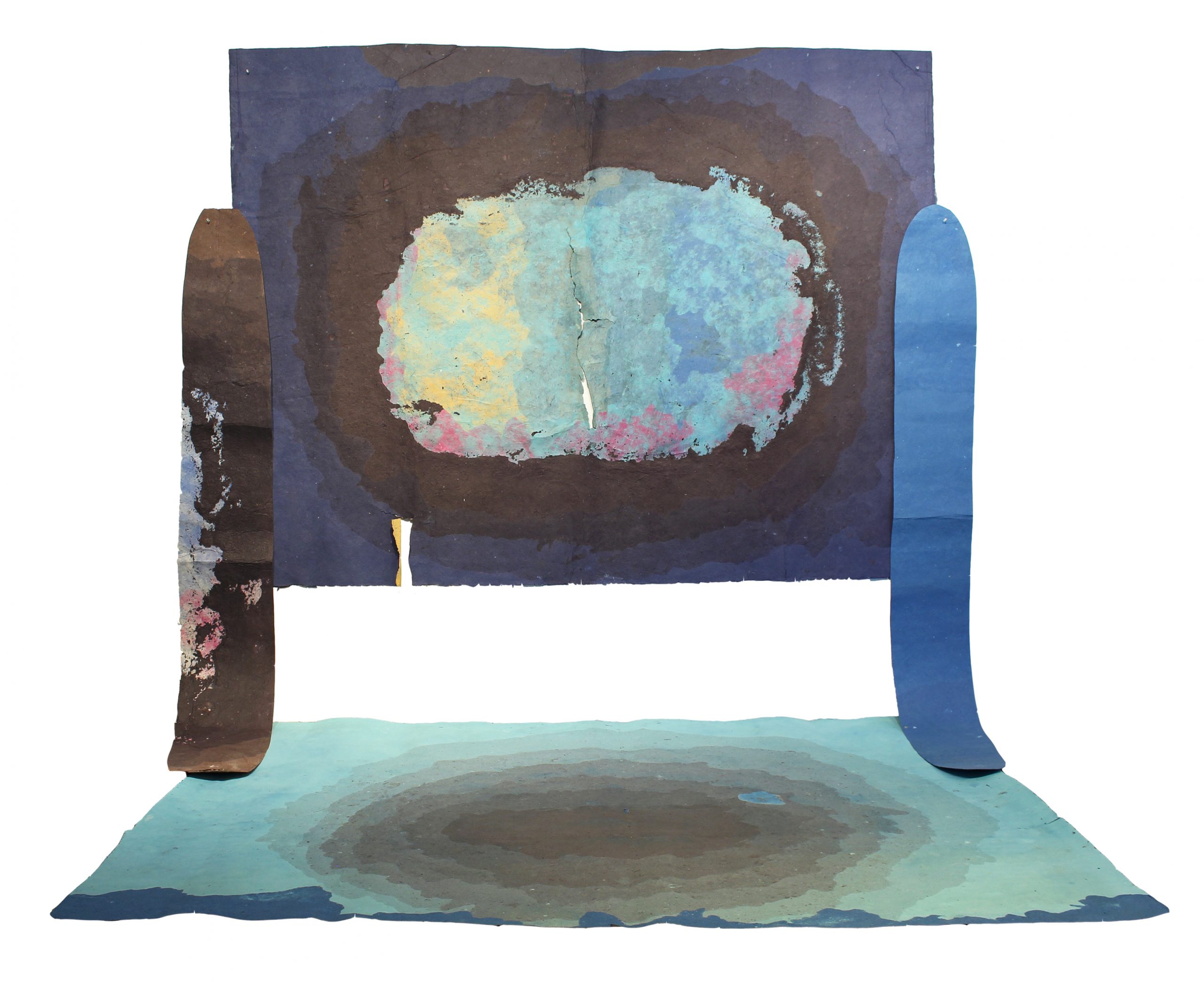

Hong Hong uses the process of papermaking to explore the reflective nature of the environment, the physical body, and the crossing of people, landscapes, culture and stories between borders in her exhibition Marrow that was presented at Artspace in New Haven, Connecticut from March 20, 2020 -to April 25, 200th. The exhibition, curated by Yell Freeman, features a series of large-scale, hand-poured paperworks made to depict the various landscapes in which she created them-from urban Chicago to rural Connecticut. Each piece uses vivid color, raw texture, and shear size that reflectively moves from wall to floor to draw an audience into the landscapes she is depicting.

Hong gives ritual to her papermaking process. She harvests the inner bark of mulberry trees at the first frost of each year, then steams and cooks it with wood ash. Her practice draws from traditional Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan papermaking processes[1] , which can be done with just the raw materials needed to make paper, deckle frames, sun and time. This allows her to be nomadic in her practice-rather than bound to a studio space- and draw influence directly from the landscapes she is working in. It also allows her to engage physically in making the paper. The softened bark is hand-beaten using a percussive process similar to tanggu, a form of ceremonial Chinese drumming that is used in a wide variety of regional opera orchestras, Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian temple ensembles, and bands. The beaten bark is pigmented and mixed with water from local water sources to create pulp that is then poured into a rectangular mold and deckle, where it dries slowly beneath the sun. Hong describes the physical nature of her work as forcing herself to be present in the spaces she is working in, in the same way one might use rituals to be present with the divine. In this process she is hyper aware of the elements of the environment that impact her work, from the humidity and sunlight of the day to the stray matter that falls into her paper as it dries. She begins each of her pours as the sun rises and concludes by the sunset. As she pours, she walks around her work, a process that she describes in terms of Buddhist circumambulation, or the act of moving around a sacred object. The pulp is poured over the surface, frequently destroying previous layers as she pours, and allows it to dry in the sun.

Hong’s work not only depicts the sites in which she created them, but also incorporates pieces of the site into the process of papermaking. As an example, her work Spell from a Trip of an Autumn Hair as Boat and Abode (2020) was made with water from the nearby St. Lawrence river. Along with the mulberry bark and paper pulp and the fiber-dye used to make the paper, she also left in any dust, foliage, hair, and other matter from the site that falls into the paper as she is making her piece, allowing them to make a mark in her final piece. There is not only reference to the landscape in their color and design of her pieces, but they also have the physical make-up of the land woven into them. These objects that are captured in her paper create impressions of both what is happening in the space as she works, as well as imply her physical touch as she works to create the paper. For Hong, incorporating these elements into her work is a natural part of the process of papermaking. They tell the story of how the rain, humidity, wind, and sun combined on that given day in the same way that the final texture and body of the paper does.

Hong describes her work in terms of bodies; the physical presence of the landscapes and earth she is referencing, the body of the sun that dries her paper, the body of the mulberry tree and how its marrow is turned pulp to form her paper, and the body of the artist making the piece. In numerous cultures, landscape is seen as an extension of a supernatural being’s body and one of the main mythological influences Hong draws from in this work is the Chinese tale of Pangu, a giant sleeping inside an egg [2]. When he wakes up, he swings his axe to separate the sky from the earth. He holds up the sky for 18,000 years, pushing it away from land a few meters each day. After he dies, his breath becomes the wind; his voice, thunder; his left eye, the sun. Bodies reflecting bodies: the body of earth reflecting the body of gods, the works reflecting the environments they were created in, the parts of the works on the ground reflecting those on the wall, and a reflection of the movement of the artists body across space as an immigrant and within the broader movement of bodies in a postcolonial landscape.

For Hong, “Manual labor returns us back into matter” (Azize Harvey, artist interview with the author via Zoom, September 13th, 2020). In the very physical and intensive process of making the paper her body deteriorates as the work is created. As she works outside, forces of heat and pressure and time and touch are allowed to act on her body. These same forces work on the bodies of her piece, where environmental conditions affect the process of creating her work. The importance of touch, mark making and the erosion of bodies can clearly be seen in her finished pieces.

Hong very specifically chose to use the bark of mulberry trees to make the pulp for her paper for each of her pieces in Marrow. The white mulberry tree was brought to the United States in 1733 as a food source for silkworms, as it was required by law at the time that every landowner in the Virginia colonies grow four trees to encourage a North American silk industry [3]. Even as the silk trade failed in the US, white mulberries continued to thrive as a non-native plant quite tolerant of drought, pollution, and poor soil. It is now considered an “invasive species” in the United States due to its ability to outcompete native red mulberry trees and spreading of harmful root diseases [4]. Hong relates the historical movement of the mulberry tree to that of Chinese immigrant workers in the US in the mid-late 1800s. Originally, Chinese immigrants were brought in as laborers in building the US economy and infrastructure and were later banned through the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (which was not repealed in the US until

1943 and then later changed to a blanket 170,000 visas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere in the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act [5]). Then, in 2018, visas to Chinese nationals were restricted, after the FBI warned of China’s efforts to undermine American economy and security, and today a trade war between the two countries continues to persist [6]. The use of mulberry bark as a medium for her papermaking process draws attention to boundaries and the process of border-crossing, particularly in the Chinese-diaspora, as well as reference back to traditional Chinese papermaking techniques.

Marrow was displayed at Artspace in New Haven, Connecticut from March 20-April 25, 2020 and while it was viewable from the street, the site itself was closed off to the public due to the Covid-19 epidemic. As Hong points out, the pandemic has really brought our attention to the idea of touch and being in a physical space with bodies. The awareness of our bodies and physicality of the work change with the absence of touch as much as with its presence.

Hong’s work in Marrow, as well as her broader body of work, physically ties her cultural, mythological and spiritual influences, and her own experiences in crossing borders and being foreign in a space into the materials and processes she chooses to use, while not necessarily forcing themselves to revolve around one influence or one theme. They become abstract reflections of the parallels between the colonial nature of the white mulberry tree in America and the history of immigration of Chinese in America, while also literally reflecting the color and shape of the pieces as they consume the floor and the walls they are presented on.

And while a viewer may not immediately draw ties to the mythology and history and the traditions of papermaking involved in her work they can be drawn in through the materiality of the work and the unique experience of being present with them enough to ask questions. And they are rewarded for their curiosity and interest in the complex histories woven into the work.

Recommended Reading

About Hong Hong

Hong Hong is an interdisciplinary artist working out of Houston, Texas. Hong was born in Hefei, China and immigrated to North Dakota with her mother at the age of ten. She earned her MFA in Painting and Drawing from University of Georgia in 2014 and her BFA from the State University of New York at Potsdam in 2011. Her work engages in site-responsive, large-scale paperworks where she uses traditional Japanese and Tibetan papermaking processes that incorporate ritual and performance into the creation of her pieces. This allows her practice to be nomadic, and she is frequently traveling to different locations in the United States to make her work.

Her projects have been exhibited at Madison Museum of Fine Art, Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, New Mexico History Museum, Real Art Ways, and Georgia Museum of Art. Hong is the recipient of grants, fellowships, and commissions from MacDowell, Yaddo, Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Vermont Studio Center, Center for the Arts at Wesleyan University, Virginia Beach Arts and Humanities Commission, Connecticut Office for the Arts, and the Edward C. & Ann T. Roberts Foundation. Hong is currently the National Endowment for the Arts Apprentice at the Morgan Art of Papermaking Conservatory & Educational Foundation in Cleveland, Ohio.

For more information, please visit: https://www.honghong.studio/

Work Cited

[1] Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin. “Raw Materials for Old Papermaking in China.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 93, no. 4 (1973): 510-19. Accessed November 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/600169.

[2] “Pan Gu: Chinese Tale of Creation – Shen Yun Performing Arts.” Pan Gu: Chinese Tale of Creation (English) | Shen Yun Performing Arts. Shen Yun Performing Arts, August 24, 2016. https://www.shenyunperformingarts.org/explore/view/article/e/URQuh8K0ciI/pan-gu-creation-china.html.

[3] Pelham Cotton, Lee. “Silk Production in the Seventeenth Century.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, February 26, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/silk-production-in-the-seventeenth-century.htm.

[4] “White Mulberry (Morus Alba).” Invasive.org. Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health, November 11, 2010. https://www.invasive.org/alien/pubs/midatlantic/moal.htm#:~:text=White%20mulberry%20invades%20forest%20edges,of%20a%20harmful%20root%20disease.

[5] Chishti, Muzaffar, Faye Hipsman, and Isabel Ball. “Fifty Years On, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Continues to Reshape the United States.” Immigration Policy Institute. Immigration Policy Institute, March 2, 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/fifty-years-1965-immigration-and-nationality-act-continues-reshape-united-states.

[6] Hong, Hong. “Statement of Practice.” Accessed November 21, 2020. https://www.honghong.studio/statementpractice.