“I have no place to take myself except painting.”

– Miyoko Ito[1]

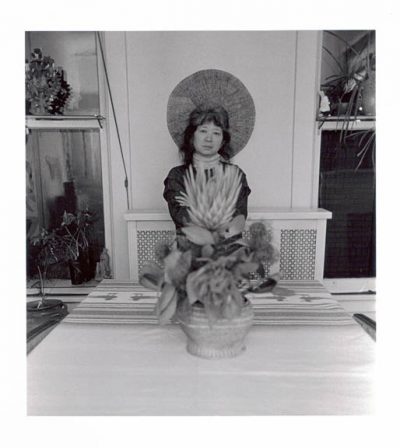

Miyoko Ito was born in Berkeley, California, to Japanese parents in 1918. Owing to her family’s limited means and a difficult housing market, she relocated to Japan as a young girl with her pregnant mother and younger sister. “Those five years are the roots of what I am right now,” she reported later, explaining that they were both “very wonderful” and “terribly traumatic.”[2] While she excelled in an arts-filled curriculum at school, her mother gave birth to a stillborn child and Ito became badly ill, for a time losing the ability to walk. Towards the end of her life, the artist experienced a nervous breakdown, and would speak about the early chapter of her childhood in these terms.

Returning to Berkeley, Ito attended high school and majored in art practice at UC Berkeley, where she studied watercolor under John Haley, Erle Loran, and Worth Ryder. Her senior year was interrupted by World War II, when she was sent to Tanforan—a San Bruno horse track turned internment camp—alongside her new husband, Harry Ichiyasu, and thousands of others under Executive Order 9066, signed by Franklin Roosevelt in 1942. Released years before her new husband, Ito briefly matriculated at Smith College before transferring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she received a scholarship but never graduated.

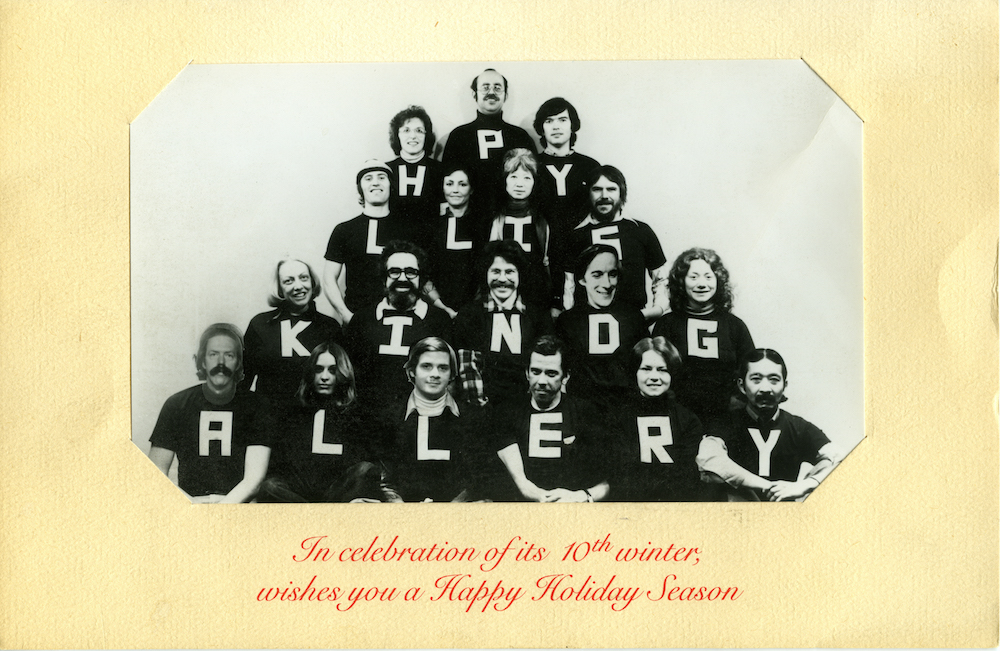

Miyoko Ito was born in Berkeley, California, to Japanese parents in 1918. As a young girl, she spent several years with her mother and sister in Japan, where she first experimented with calligraphy and painting. Ito followed in her father’s footsteps to the University of California, Berkeley, where she studied watercolor under John Haley, Erle Loran, and Worth Ryder. Months before her graduation in 1942, Ito was sent to Tanforan, an internment camp south of San Francisco. Released years before her new husband, Ito briefly matriculated at Smith College before transferring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she received a scholarship but never graduated. Although her efforts were highly susceptible to regionalization, Ito participated in the 1975 Whitney Biennial and was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Renaissance Society in 1980. She was represented by Phyllis Kind Gallery in Chicago and New York from the late 1960s through her death in 1983. Recent exhibitions include solo presentations at Artists Space, New York, 2018; University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2017; Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York, 2014 and 2006; VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin, 2012; and No Vacancies, a group presentation at Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, 2015.

Chicago was a supportive environment for women artists and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—unique for its female faculty and supporting non-European-centric art history courses—admitted women and artists of color by the end of the late 19th century.[3] Kathleen Blackshear, an artist and art historian who integrated works and cultures then considered “primitive” or otherwise off-canon into her curricula, especially influenced Ito. Cited as “the first woman to wear pants in her small southern hometown” [4] of Novasota, Texas, Blackshear arrived to Chicago in 1924 to study at SAIC and began teaching there just two years later. It was not uncommon for the young professor to shepherd students to the Field Museum of Natural History, the Oriental Institute, Shedd Aquarium, and even the zoo and planetarium.

Blackshear sought to examine “systems of abstract patterning in the natural world and in manufactured objects,”[5] herself taking a cue from Helen Gardner, the pathbreaking professor of SAIC’s first art history course and author of the influential book, Art though the Ages: An Introduction to Its History and Significance (1926). Gardner greatly inspired a group of postwar figural painters in the 1940s including Leon Golub, Theodore Halkin, Evelyn Statsinger, and others who came to be known as the Monster Roster. Depictions of strange, hybrid human-animal creatures, inspired critics “to explain that the new generation of Chicagoans made monsters and trafficked in horror and the abject,[6] as curator Bob Cozzolino has written.

Though Ito had distinct aesthetic concerns, she and several Monster Roster artists played a significant role in the creation of Exhibition Momentum (1948–1957), a self-organized group that “posited a way to work around old-guard authority and the dearth of commercial spaces in Chicago,” that ultimately proved unsustainable due to “conflicting aims and infighting.”[7] Momentum organized exhibitions at six different venues and solicited high profile national jurors, including Betty Parsons and Clement Greenberg.[8]

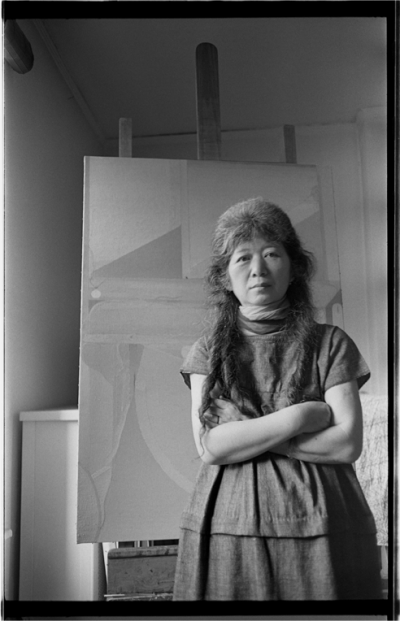

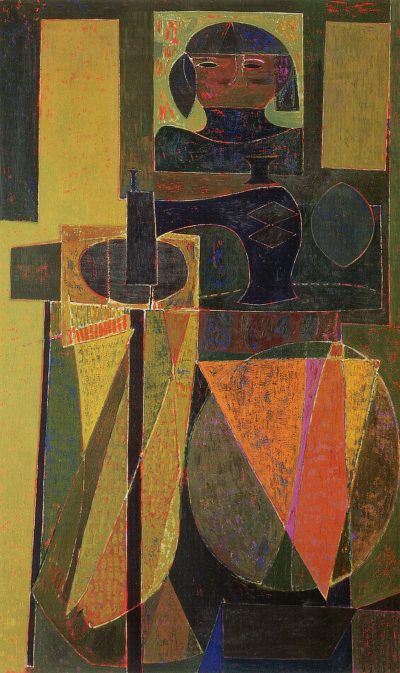

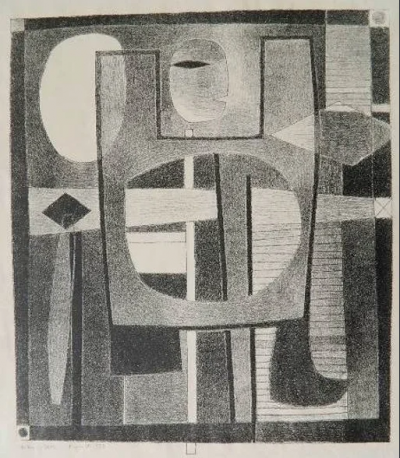

In the early days of Momentum, Ito abandoned the watercolor practice informed by the patterns and textures of Synthetic Cubism that had defined her education. Instead, the artist employed various printmaking methods, including lithography, a medium she first explored as a resident at Oxbow Art Colony, a summer art school in Michigan affiliated with SAIC, and oil on canvas. On several occasions, the artist rendered precisely the same quasi-representational content across multiple media. Beginning at this time, Ito’s work was included in large—and largely anonymous—annual juried exhibitions around the country, including repeat appearances at the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Art (later the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Her first daughter, Elissa, was born in 1949, the same year as her first solo exhibition at the Palmer House Galleries in Chicago. Her son, Alan, was born the following year. “I was pretty much obscure in the ‘50s,” the artist notes, “raising two children and also staying pretty much to myself, too.”[9] She did, however, maintain friendships with artists Vera Berdich, Walter Boyer, Whitney Halstead, Tom Kapsalis, and Evelyn Statsinger. The representational content of her work, such as figures and domestic objects, was traded for a geometrically rigid, collage-like formalism in brackish shades of green, blue, orange, and yellow. Further, she developed an underpainting technique that remained critical for the remainder of her practice in which improvisatory drawings in red, green, and charcoal formed the foundations of emergent paintings, the lines serving as shadowy gaps between color forms.

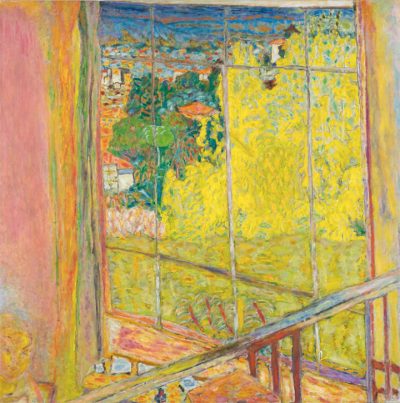

Toward the end of the decade, she altered her formal approach once again as sharp corners grew rounded and compositions turned bodily and tubular. Her style, defined by some as “abstract impressionism,”[10] was informed by the surfaces of Pierre Bonnard and the influence of Surrealism.[11] In an effort to share her effortd with an immediate community, Ito founded Superior Street Gallery (1959–1961) with artist Ellen Lanyon and others, an important but short-lived exhibition space in part supported by Joseph R. Shapiro, who soon became the first president of Museum of Contemporary Art.

Kalamazoo, from 1959, is emblematic of her early, self-assured experiments with oil on canvas. The work depicts a menagerie of wide-eyed figures in a thick, earthy application of mid-century browns, blues, and yellows. Its title, which references a town just over the Michigan border from Illinois, may have sounded otherworldly to a Midwestern transplant seeking inspiration. A sense of buoyancy and depth foreshadows the floating network of wiggles, threads, dots, portals, and tufts that would populate her efforts for decades.

Slightly later works like Step by Step (1962) introduced not only a brighter palate, but seductive color gradient backgrounds, a hugely significant innovation conjuring a sense of depth. Forms no longer play on the surface of the canvas, but instead come alive against the recession of space and passage of time. Titles like Step by Step simultaneously reflect the pedestrian and psychological.

From the early 1970s, self-organized modes of presentation and message-in-a-bottle submissions gave way to more nuanced participation at a number of nimble and exciting Chicago institutions, including a solo exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1971, and the 1972 landmark exhibition Chicago Imagist Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The term “Imagist” itself is confused and complex, and her participation in the latter show has more to do with her inclusion in critic and artist Franz Schulze’s book Fantastic Images: Chicago Art Since 1945, published the same year, than any connection to what came to be known as Chicago Imagist artwork later in the decade. While the word has become a kind of shorthand for much experimental work coming from Chicago, there was a disconnect between the artwork emanating from SAIC from 1945 to the mid-1960s and the rise of the next generation of Chicago artists. In the context of representation and given the rise of abstract expressionism, her friend, the artist Vera Klement, notes that at this time Chicago was “polarized between imagism and abstraction. But Miyoko had taken her place on a higher ledge, a precarious point of balance between the two.”[12]

Ito was an early charge of legendary dealer Phyllis Kind, who afforded the artist a solo exhibition at her Chicago gallery in 1973. Later that decade, Ito had significant exposure in New York, including an appearance in the 1975 Whitney Biennial followed that same year by a solo exhibition at the esteemed Kornblee Gallery, which also presented the work of Dan Flavin, Malcolm Morley, and Betty Parsons. Kind, who herself opened a New York Gallery shortly thereafter, presented a solo exhibition of Ito’s work in 1978. Her practice developed from Hyde Park, where she had a home studio, and during nearly a dozen fellowships at McDowell Colony beginning in 1970 and further trips to Oxbow, settings that allowed for quiet, focus, and camaraderie.

Kind came to represent many of the now internationally recognized next-generation-Imagists, including Roger Brown, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, and Barbara Rossi, among others. Nutt recalls that Kind’s embrace of Ito—already a mature artist—motivated him and wife Nilsson to sign up on her growing artist roster, one that became critical to Chicago’s art history.[13]

Though a generation older than the stars of a movement known for its offbeat, comic-book iconography, Ito shared their zeal for the subliminal juxtaposition, logic-defying representation and technical precision of Surrealism. Ito and the younger artists successfully fused Pop Art’s feverish palette with an eccentric, outsider air. A sense of discovery was prized. “When I approach a canvas, I try to as much as possible keep my mind blank,” Ito remarked.[14]

That said, Ito was an outsider in age, disposition, and background from this group, and her union of physical and metaphysical worlds would have been too precious for many of the urbane up-and-comers. Titles like Oracle, Shrine, Dusk, Narcissa, and Steps signal an interest in time, ritual, repetition, and myth. Ito’s efforts are more aligned with the materially rich and visionary work of painters such as Forrest Bess and Helen Frankenthaler, her contemporaries, or Arthur Dove and Giorgio Morandi, a generation older.

The artist hit an astonishingly unique stride from the 1970s until the end of her life with searching explorations of self-portraiture and place. At once first person and topographic in their construction, many works from this period overlay a mountainous, bust-like figure against a distant horizon of saturated color. While references to landscape painting and architecture are overt, Ito’s highly structured, never-quite-symmetrical compositions constitute a profound mapping of the psyche, oscillating between confinement and expanse. In a palette that warms over time, vertical stacks of tubes, bars, and mounds are rendered in delicate fades of color and subtle modulations in tone. A picture emerges of an artist endeavoring to position herself in relation to hazy and remote surroundings. “I have no place to take myself except painting,” Ito revealed in a 1978 interview.[15]

The compartmentalized spaces of her most fertile period are organic and exact, like dreams recalled in unusual detail. Works like Interior Presence, 1971; and Heart of Hearts, Basking, 1973, portray furniture-like elements slipping into abstraction, while simultaneously suggesting a mind becoming a closet or drawer—that is, an apparatus for the arrangement of things, sometimes shared but often closed or concealed. Not explicitly political, the tension between domestic and subjective interiority, the act of self-portraiture, and her collage-like practice are nonetheless in tune with the second-wave feminism of the time.

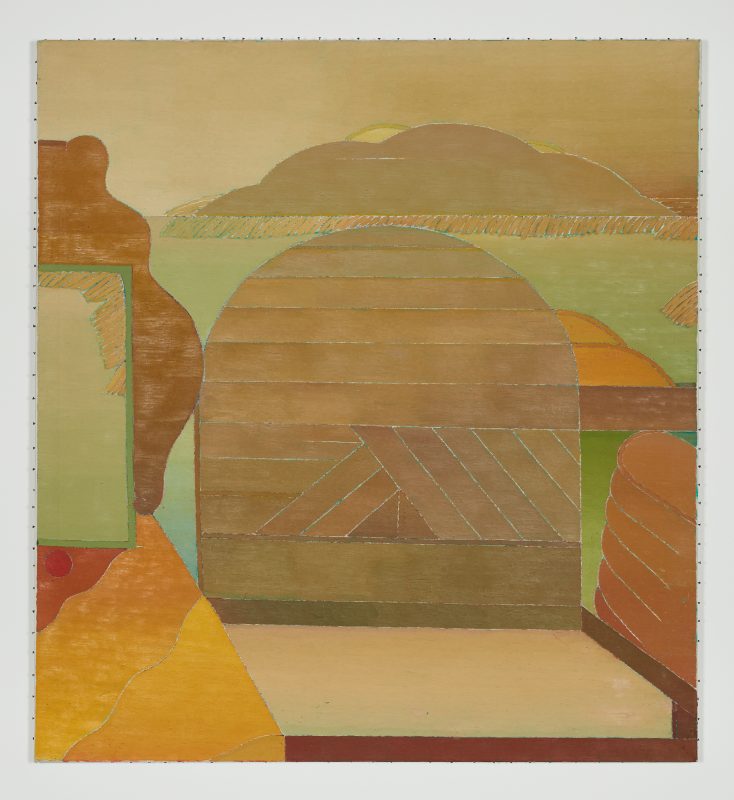

The title of Todoroki, 1974, is a Japanese surname common to the Nagano Prefecture, where it exists as a location. It is also a remote waterfall in the Okinawa Prefecture, and, neatly, in English translates to “rumble” or “resound.” The painting emphasizes the overlapping of name, place, and sound, and is indicative of Ito’s unfixed and synesthetic approach. Thick, horizontal lines support the picture as stretcher bars support a frame.

Later works like Center Stage, 1980, and Iliad, 1981, grow increasingly abstract and celestial, the drama at their core not just hollow, but indeterminate. A more profound sense of space is signaled, as if the theater itself, unsure of its role without actors, begins to come undone. Ever warmer, they are rendered in mauve, pine, summer orange, and countless shades of blue. Narcissa (1982) and Byzantium (1983) describe rigorous self-examination while hinting, for the first time in many years, at a combination of bodies. Layers stack vertically in mounds, slides, and bars, like video games of hallucinatory origin.

Numerous canvases are affixed to their stretcher bars with half-driven tacks, apparently the result of Ito’s wish to remove and continue working on various paintings over time. The raised tacks remain, however, even in many “finished” works—as if a halo beyond the canvas edge. As critic John Yau notes, they “recall the need to be able to leave quickly with what is most precious, to be able to roll it up rather than leave it behind.”[16] They speak to a violent and vulnerable admission of the mere thingness of painting, and in turn, life.

Although her efforts were highly susceptible to regionalization, Ito was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago in 1980. She died from cancer in 1983. While commercial galleries like Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York, and VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin, mounted solo presentations of her work in the last 20 years, Miyoko Ito / MATRIX 267, an exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in 2017, marked the first solo presentation of Ito’s work in her hometown and the first in a public institution in nearly forty years. Not a decisive survey, MATRIX 267 primarily brought together a group works painted in the last dozen years of the artist’s life.

Although it is difficult to explicitly track Ito’s relationship with her native Berkeley through her work, traces of her hometown appear in Untitled 126 (1970). The relatively subdued canvas foregrounds a dome-headed object surveying a strikingly familiar landscape, as if Ito were watching the sun slowly set beyond the hills and blue-green water of her childhood. Her singular vision, in this work and in her practice more broadly, reminds us not only of our inseparability from the natural world, but that human interiors are just as vast and unknowable as any vista.

Heart of Hearts, a version of the MATRIX exhibition, was mounted the following year at Artists Space, an important not-for-profit institution in downtown Manhattan. The show brought many reviews and accolades to the artist’s under-known practice. Though her star may continue to rise after her death, one wishes the artist might have celebrated her uncommon achievement with a wider public during her lifetime.

Author’s Bio

Jordan Stein is a curator and writer based in San Francisco whose practice aims to link the past and present through the varied presentation of objects, archives, and ideas. Stein is the author of Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo’s Estocada and Other Pieces (Sobersove Press, 2021). He operates Cushion Works, a project space for exhibitions and events, serves as a Curator at KADIST, and has organized exhibitions independently at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Artists Space (New York), the Renaissance Society (Chicago), San Francisco City Hall, Yale Union (Portland, OR), Matthew Marks Gallery (New York), Fraenkel Gallery (San Francisco), and more. Stein is a co-founder of the interdisciplinary collaborative group Will Brown, which realized over three dozen exhibitions and programs in their Mission District storefront from 2012–2015. With Will Brown, he is the author of Bruce Conner: Brass Handles, and with Jason Fulford is the editor of Where to Score, a collection of hippie-era classified advertisements. Press for his recent projects has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, Artforum, Art in America, Frieze, Los Angeles Review of Books, San Francisco Chronicle, and KQED.

Works Cited

[1] “Miyoko Ito: An Interview,” Blumenthal/Horsfield, Video Data Bank, 1978. Transcript later published as Miyoko Ito, Profile, Vol. 4, No. 1, January 1984, 19.

[2] Oral History interview with Miyoko Ito, July 20, 1978. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-miyoko-ito-11656#transcript.

[3] “A State of Independence in Chicago,” in The Female Gaze, Women Artists Making Their World, ed. Cozzolino (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 2012), 63-75.

[4] Susan Sensemann, “Kathleen Blackshear,” in Women Building Chicago 1790-1990, ed. Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2001), 84

[5] ibid., 84

[6] Robert Cozzolino, “Raw Nerves, 1948—1973,” in Art in Chicago, A History from the Fire to Now, ed. Cozzolino (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 146

[7] ibid., 136

[8] ibid., 140

[9] Horsfield, Profile, 10

[10] ibid., 8

[11] ibid., 9

[12] Horsfield, Profile, 27

[13] Jim Nutt, conversation with the author, September 19, 2016

[14] Horsfield, Profile, 15

[15] Horsfield, Profile, 19

[16] John Yau, “Artseen: Miyoko Ito,” Brooklyn Rail, May 9, 2006, https://brooklynrail.org/2006/05/artseen/miyoko-ito