How is autobiography presented in museum exhibitions? In 2012, I curated an artist’s home collection in the 4,000 square foot gallery of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. Believing strongly that objects and their arrangements in a home can offer as much—if not more—information than a traditionally written biography, Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values endeavored to understand the artist’s biography through the things he surrounded himself with. Below are some of the thoughts and theories that help support the curation of the show.

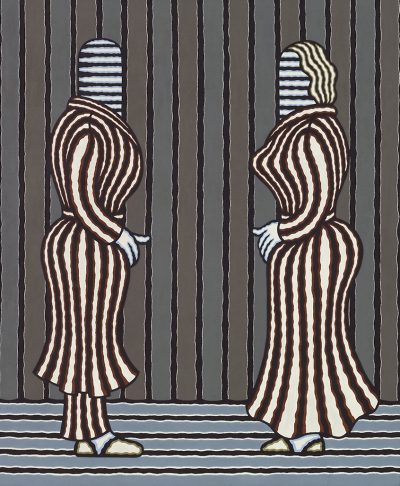

Ray Yoshida (1930-2009) was an artist and faculty member of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1958 to 2003. In 2010, the School of the Art Institute hosted the 135-work exhibition Touch and Go: Ray Yoshida and his Spheres of Influence, the largest and most extensive gathering of works ever devoted to Yoshida’s influential career as a painter and collage maker. It was also the first large-scale show in Chicago since the artist’s death in 2009, comprehensively examining his oeuvre and its relation to his life at SAIC as a professor, student, and colleague. In talking about Yoshida, John Corbett, co-curator of the exhibition, said, “He was, in this sense, the progenitor of a whole new sensibility, a visual vocabulary built on formal sensitivity and input from a range of vernacular resources.”[1]

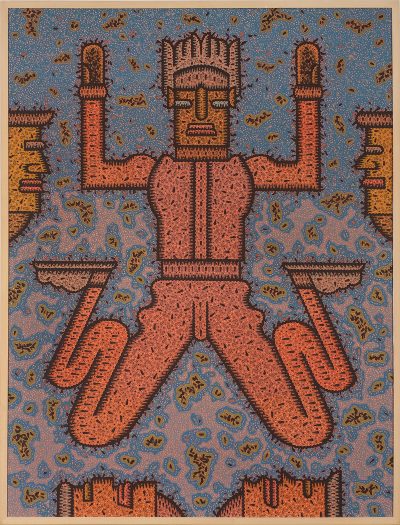

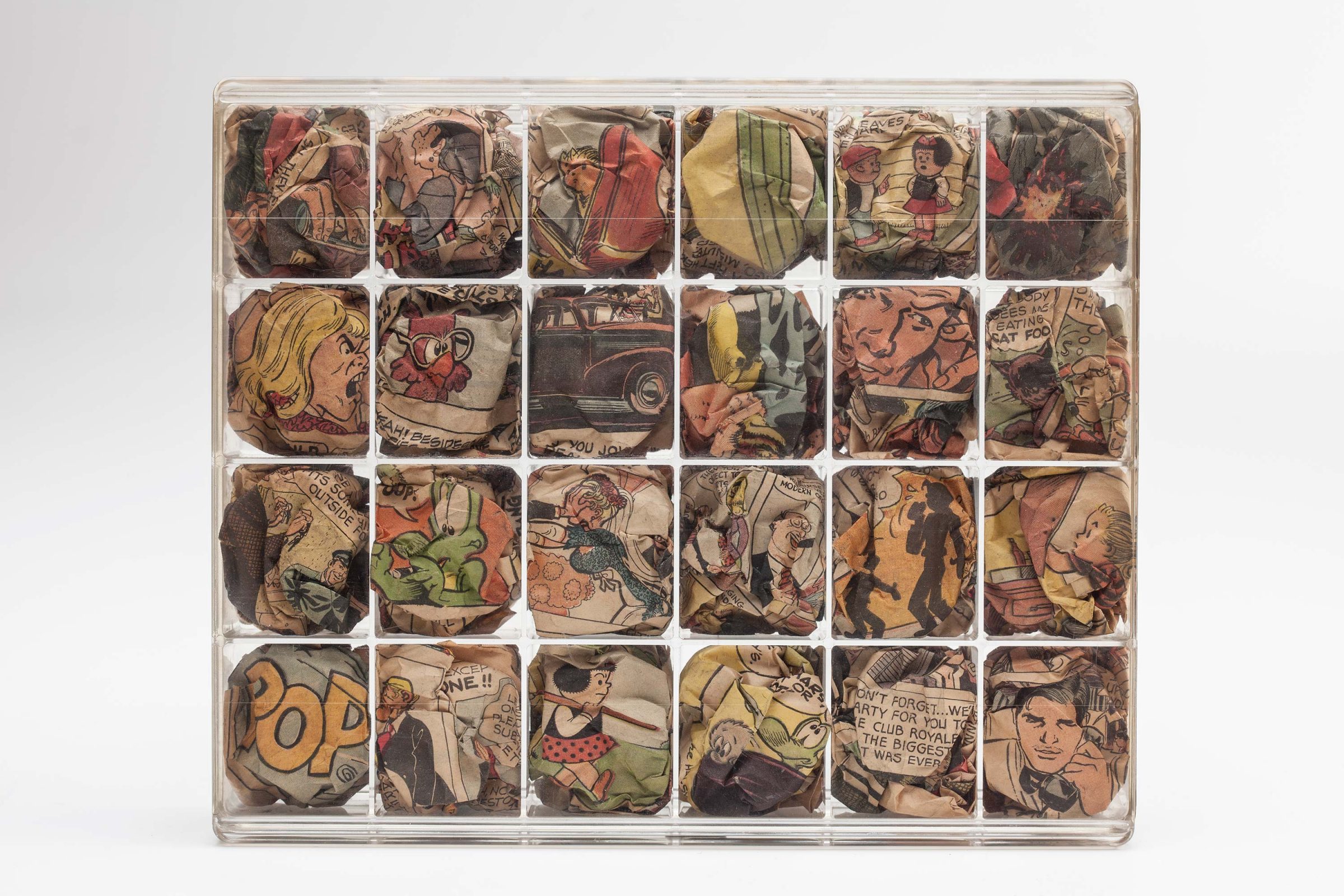

Yoshida scoured the city of Chicago for objects, artworks and artifacts that expressed the everyday. As opposed to objects with wider appeal or distribution, Yoshida was drawn to the more idiosyncratic and local. In many respects, Yoshida’s practice was to look beyond the traditions of Western painting for sources to inform his work and ignite that practice in others. This led to the creation of a formidable, elaborate and meaningful home collection. Housed at 1944 North Wood Street, it ranged from drawings by self-taught artists Joseph Yoakum and Jesse Howard to tramp art, tattoo sheets, and whirly-gigs; from mass-produced metal toys and postcards to store signage; from thrift store treasures to African masks; and from works of art by esteemed colleagues to religious ex-votos. Yoshida used his findings as elements in a visual jigsaw puzzle with unlimited solutions. For him, the poetry of bricolage, the art of constructing a work from eclectic images and objects, became a way of life. This innovative artist also played a seminal role in the elevation of vernacular aesthetics and the commingling of fine art with the entirety of visual culture.

1930 Raymond “Ray” Kakuo Yoshida was born in Kapaa, Hawaii

1948-1950 Attends University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

Serves in the army during the Korean War for two years

1953 Earns BFA from School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC)

1958 Earns MFA from Syracuse University, New York

1959 Teaches at SAIC from 1959 to 2005

1960 First Solo exhibition at the Middle Hall Gallery, Rockford, Ill.

1975-1996 Exhibits at Phyllis Kind Gallery

1998 Retrospective at The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, The Chicago Cultural Center, and the Madison Art Center.

2009 Artist passes away in Kauai, Hawaii of cancer

2009 Retrospective Touch and Go: Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence at the SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries.

2013, the exhibition “Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values” at John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan Wisconsin

Collections:

The Art Institute of Chicago

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, Chicago

Forlorn Objects and the Artist

For Yoshida, Chicago was the city of objects and images—a never-ending range of things and connections that triggered ideas and creative energy. Especially pleasing to him was rescuing what he perceived as a forlorn object, with little to recommend it, likely to have been passed over by many before him.[2] These objects and works of art were assembled before a Chicago backdrop of prevailing and traditional attitudes that drew boundaries between art as high/low, fine/folk, craft/factory, etc.—dichotomies that Yoshida rejected. Preferring ethnographic artifacts found at the Field Museum, or unique finds at flea markets over the fine art presented at the Art Institute of Chicago or in high end private collections, he encouraged SAIC students to seek inspiration in unlikely places—a lesson that was adopted by many generations of artists.[3] As Chicago artist and fellow SAIC instructor, Barbara Rossi, says, “We would look at the rejected and understand what we could learn from it before it disappeared. Sometimes that moment was very beautiful.”[4] Living with these “misplaced muses” was integral to Yoshida’s artistic practice.[5] Through his collection, Yoshida was offering a new way of looking and valuing these objects and works of art, even if they had yet to be valued by the larger art community. Folk art, manufactured goods, fine art, tribal pieces were all extracted from their previous contexts and introduced to the collection, open for new interpretations.

Following his death in 2009, Yoshida’s collection was dismantled and, along with many of his paintings and collages, was dispersed to various cultural institutions. The collection is currently housed at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC) and a large portion was exhibited in 2013 in an exhibition titled Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values. As the curator of that exhibition, I sought to understand Ray Yoshida through the lens of his collection.

A variety of definitions and insights were employed in this endeavor. Firstly, Jules Prown’s definition of material culture was considered:

…the study through artifacts of the beliefs-values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions of a particular community or society at a given time. The term material culture is also frequently used to refer to artifacts themselves, to the body of material available for such study. [6]

Understanding Ray Yoshida through his collection meant I was operating from the belief that material culture research is the study of culture through its artifacts and the underlying premise that anything modified by man reflects, indirectly or directly, the beliefs of the individual who created it and by extension, the community in which he or she belongs. Through the examination of the objects in his collection, we learn what was evocative to Yoshida and how his relationship with objects ignited and sustained an art practice for over five decades. Our relationship to the accumulation of objects is as profound and as significant as our relationship to each other, to language, and to time and space, and as complex. Meaning is a matter of social construction, the ideological basis of which can be unraveled, or deconstructed. It is my belief that Yoshida carefully constructed his environment to assert his identity as a teacher and artist and this exhibition was an opportunity to illustrate this belief.

I also applied Jennifer Gonzales’ term of autotopography, defined in Prosthetic Territories, Politics and Hypertechnologies. An autotopography can exist in many forms: “a careful, visual arrangement of mementos and heirlooms, on the one hand, and a jumbled, hidden assembly of dusty and unkempt objects, on the other, can both constitute a material memory landscape.”[7]

Moreover, Gonzales notes, an autotopography draws from life events and cultural identity to build a self-representation as a material and tactical act of personal reflection “…just as a written autobiography is a series of narrated of events, fantasies and identification, so too an autopography forms a spatial representation of important relations and past events.”

The curatorial task of re-assembling a dismantled collection and bringing together the integral aspects of the collection in order to deepen our knowledge of the artist and his methods was also guided by Latour’s notion of “reassembling the social.” That is, I followed the artist’s network to achieve a less linear and more expansive reading on the collection.[8] In Reassembling the Social, Latour reevaluates the ambiguous term “the social.” He claims that the dominant trend within sociology has been to conceive of the social as a given totality, “always already there” which provides a solid base for understanding any other phenomena.[9] Against this tendency, Latour contends that it is the social itself which requires explanation and insists that we must always ask how it is constituted; through which associations, involving what actors.[10]Only to the extent that the thinker pays attention to all the agents and relations involved in a given assemblage, he writes, does she have any right to posit a unifying theory of the whole.[11] This helped guide my focus on the actants and locations that informed the collection, starting with the site where many of the objects were sourced—the Maxwell Street Market.

Maxwell Street Market

In the neighborhood that was home to Chicago’s Maxwell Street Market, the residents and businesses are now gone. Almost all the building that lined Roosevelt, Maxwell, Halsted, and the side streets have been razed. The market itself, one of the city’s distinct landmarks, could not stand up to the irrevocable changes brought by the Dan Ryan Expressway and the urban renewal projects initiated by the University of Illinois at Chicago in the 1990s.[12] Once a pulsating public market for the immigrant and working class populations of Chicago—a living incubator of culture, community, and merchandise, where the value of the goods was subjective and capturing a bargain required a keen eye and bartering skills—it has now become flattened and anesthetized in the name of progress. Maxwell Street was more than an outdoor market. It spoke to the fabric of community and the work ethic of the Midwest, and it thrummed with the tenacious sounds of Chicago blues and gospel music. For a small group of Chicago artists in the 1960s, it also represented the thrill of the chase, the promise of unknown treasures, and the chance to rescue a snubbed or undervalued object. Intuitive, ravenous, and competitive, these artists were on the hunt, honing their skills and deepening their ability to not just look, but to see. Maxwell provided a tactile experience, offering everything from the particular to the peculiar, the familiar to the fantastic.

Ray Yoshida foraged Maxwell Street with the commitment and zeal of an insatiable artist. Not always knowing what the tables and blankets strewn on the ground would support, but trusting that in his role of an artist, he would be able to re-value the ordinary into something new and strange again. The “trash treasures” became the catalysts for his work as a painter, collagist, and teacher. Offering a new setting to discuss art making, a rug beater becomes a model for line, shape, and form; the pile of hubcaps, a perfect specimen to explore shading and perspective; a frog-shaped fishing lure transforms into a discussion on humor and purpose. For Yoshida, the transformation of shape and the concurrent blurring of meanings, and the allusive but endless potential of a thing was paramount. Rather than seeing things for what they were, he freed himself into the investigation of what things could be. And what particular detail of the thing propelled itself to a new more oblique identity.

Seeing vs Looking

Yoshida encouraged his students at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago to do the same—to look far beyond the “art world” for material and inspiration and to trust your eye in the search for the unique amongst the ubiquitous. He asked of them to focus on wherever there was interest and to translate that interest into one’s work. Whether it be on the streets of Chicago, in vernacular architecture or in observing people passing by, he sought to train students’ eyes to see what fed their practice. During his tenure at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—one of most the most important actants in his life—Yoshida taught and mentored several generations of artists. His role as a strong educator resonates deeply with many of his students, including but not exclusively, artists who became known as the Chicago Imagists, a Chicago-based group of artists who that favored surrealism, fantasy, and off-the-mark humor.

Yoshida and fellow SAIC instructor Whitney Halstead encouraged students to open their eyes and draw inspiration from their daily environment. The Imagists’ use of the vernacular was filtered through a strongly personal response. Commercial and popular sources are never used “straight” but as catalysts for the artists’ emotionally charged transformations. Perhaps themselves outsiders in relation to the New York Pop Art and abstract expressionist movements, Chicago artists did not look to the hyped conventions of the New York art world, instead they were influenced by self-taught art, non-traditional art, comic books, pulp fiction, advertisements, and artifacts. They also shared a common interest in craftsmanship and DIY projects, showing that their source material transcended their identity as derivative; these works were appreciated for technique, visual design, and imagery.

An Artist’s Life in his Collection

Although he is credited for the mentoring and teaching of many artists, little is known or written about Yoshida’s personal life. Yoshida himself was a very private person, as was his collection. In an interview with Jim Dempsey, co-curator of the 2009 exhibition Touch and Go: Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence, Dempsey says:

I think that was kind of a way that Ray could talk in an artful way about things that maybe didnʼt have directly to do with his work, or him directly. Because he was always, from what I gathered, reluctant to really talk about things he was doing. ʻYou know whatʼs going on in the studio, Ray?ʼ ʻOh you donʼt need to know that,ʼ or ‘What are you working on?’ ‘Oh nothing youʼre interested in.’ You know, very self-effacing and shy about the work but if he could get very excited and talkative about something right next to the work, most often his collection. I think that was a way in talking about his process somehow without having to claim yourself an artist. You could shift it over, just a little bit, to talk about those things and use the same types of muscles but avoid really confronting who you are as an artist but confront the things that make you think about art or the world in an artful way. That seemed easy for Ray. Talking about the direct interaction with what he was making seemed, not difficult for Ray, but something that he didnʼt seem to delve into much.[13]

In focusing on his collection, he was telling about his ways of seeing, the steps that go into making. But it was also a way for his friends, colleagues, and students to understand him as a person. Jim Nutt, fellow Chicago artist, wrote for the catalog Ray Yoshida: A retrospective 1968-1998.[14] He called a visit to Yoshida’s home a “visual treat” but that there was only enough furniture to accommodate his own personal needs, encouraging a visit of short duration. Never following the logic of a traditional collection, Nutt referred to Yoshida’s collection as an “overwhelming wealth of connections and visual expression.”[15] Yet he struggled to understand Yoshida himself, calling him a “challenging presence,” but that “things happen when [he is] around,” firmly believing that his “trash treasures” come to life whenever he’s there, and not when he’s gone, thus stressing the importance of the artist’s eye and presence in the importance of the collection.[16]

Using his home at 1944 Wood Street as a point of departure, research on Yoshida and his collection in Chicago was primarily conducted with the assistance of films, interviews, catalogs, and archival materials from Yoshida’s estate, as well as documents found in the Roger Brown Study Collection archive. In this research, Yoshida and his collection are discussed primarily as a representative of a Chicago aesthetic, as a marker of a specific time in Chicago, and as a way of understanding a private and complex man and his great ability to engage with the evocative nature of objects.

In 1980, Roger Brown (1941-1997), Chicago artist and student of Yoshida’s, wrote a brief history of the setting of the Chicago art scene and the factors that contributed to its establishment. In an article entitled “Rantings and Recollections,” Brown states the birth of the Chicago art scene as the 1960s, in what he called a significant movement in recent art history.[17] He wrote that the movement was concerned with the making of art as an “individual and very personal endeavor….Inspiration is taken from the raw, direct art of the naive or folk artist whose work is unencumbered with pretentions to “high art,” and from the art of primitive societies which expresses a spiritual necessity for its very existence.”[18] Brown further describes the movement as the synthesis of naive art with interest in popular American arts, including comics and toys, and an interest in the early Renaissance and oriental art “in[to] unique and individual expressions of their own.”[19]

Although he acknowledges that throughout the sixties, various artists were beginning to look in non-traditional places for art and inspiration, citing Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol as examples, the Chicago Imagists dealt with popular culture not only as a source, but as art in its own right. Speaking to an intensity that Chicago artists shared, he credits the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Ray Yoshida, among other reasons, for the fervor with which they approached their practice. In talking of his own career, Brown describes a moment when his practice moved into a more defined place, when he began drawing from memory and experience, creating paintings related to theater prosceniums. He writes that he was “influenced by Ray’s emphasis on drawing from personal experience so that one’s art and life merge.”[20] Most importantly, Brown collected art by his peers in Chicago, works by self-taught artists, ethnographphic art and objects from popular culture, a practice inspired by Yoshida. Brown and Yoshida were close colleagues and friends and often scoured the city of Chicago together, looking for objects to rescue.

Roger Brown’s collection is often compared to Yoshida’s collection and discussed in terms of a particular time and place of Chicago art history, 1960-1990s. Toward the end of his life, Brown gave his home collection to SAIC, so the school could use the gifts to perpetuate the creative process for successive generations of students and faculty. Currently, the Roger Brown Study Collection—preserved as Brown lived in it, as his Artists’ Museum—and the RBSC Archive provide an important resource for primary research that includes various works ranging from contemporary art and travel souvenirs to sketchbooks and personal and professional correspondence. Explicit instructions for the Yoshida collection were not given in his will, but those close to Yoshida stressed the importance of this collection, as the seed that pollinated a generation of artists.[21]

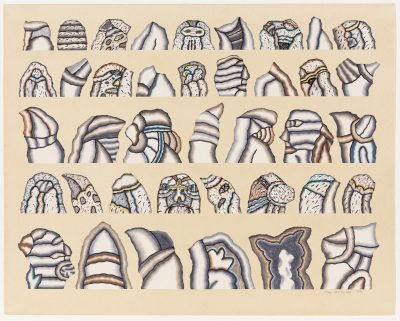

In Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett defines the term “thing power” as the curious ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle.”[22] Yoshida would have viewed his collection as having thing-power, the evocative yet elusive stimuli finding their way into paintings such as Extraordinary Values (c.1970), for which the JMKAC exhibition was titled. Among most Chicago artists, Yoshida perhaps most persistently applied himself to the endless potentials of the things we see. A 1990 film entitled, “The Individuality of the Inanimate Object: The Collection of the Ray Yoshida,” offers insight into his interests:

I’m interested in permutations of one idea or possible form. And somehow seeing them together in a group heightens their interest for me. And, well, the idea of being able to change their relationships to one another just by physically moving them around. I mean that’s why I guess I have the African masks sort of isolated as a group, and the Mexican masks in the back and the New Guinea wall and so forth. It just, well I guess, you know, these, these are some of the recent interests. And I hunt for them whenever it’s possible to find them.[23]

More than collecting commemorative stamps or spoons, Yoshida was seeking out thing-power as an artist. The Yoshida collection recognizes rarity and richness in the things in every day life. He found discarded objects, re-valued them as personal source material and re-arranged them to create a conversation, meant to inspire his work and his teaching. Yoshida elaborated on this in a 1989 interview:

I guess it has to do with…all those visual elements that…sometimes it’s line, color, form, humor … awkwardness. There’s so many things that … sometimes even elegance … I guess it all boils down to the fact that the piece has to, needs to possess a certain identity, individuality as an artifact. You know, the individuality of the inanimate object, I guess, the, you know, that presence that you just feel, that nothing else is like it, nothing else in the world is like it. So the paintings sort of evolve, and, and I think indicate the transformation, the recent transformations indicate an interest or a relationship to some of the things that I live with.[24]

Collecting is a way of linking the past, present, and future. Werner Muensterberger, in Collecting: An Unruly Passion defines collecting as “the selecting, gathering, and keeping of objects of subjective value.”[25] Emphasizing the subjective aspect of the value takes a person to a realm where intuition and instinct reign. The assemblage of the seemingly incongruous objects into a totality evokes the satisfying metaphors of wholeness and unity, and the containment or display of what is valuable involves the very same questions of form and function that any artist must ask when creating work; form, function, line, color, etc. Collecting these objects and artworks reinforced Yoshida’s identity as an artist. These objects in Yoshida’s surroundings were cues for him to create, to paint, to meditate on angles and features, and then translate that information into his collages, drawings, and paintings. The transformation of shape and changing of meaning were vital to his practice. Summoning spontaneous rituals or changing the appearance, form, or context of an object resulted in works of art that were at once familiar and new to the viewer, and can be visited for new observations and discoveries.

Yoshida would have multiples of the same object in his collection, or would place unlikely objects next to each other as a way to “undo” the object’s previous role and offer a more dynamic perspective. The expressive symmetry of his New Guinea masks, the sharp profiles of the tramp art are seen in several of Yoshida’s paintings. The “sum of the parts” battle occurring in the memory jars or tattoo flash sheets resonate in his paintings and collages, exposing the negative space as much as the mysterious forms suspended within. The expressive symmetry of Kachinas or African masks, and the rigid profiles of the free-standing wooden ash tray holders or smoking stands are echoed in Yoshida’s paintings. Tenaciously applying himself to the endless potentials of metamorphic form and the shifting of shape and placement, his collages of images cut from comic papers were rearranged to suggest new visual events. Yoshida’s paintings have been described as “bits of mysterious narrative” or “frames of a lost comic strip,” analogies that also apply to the various artifacts removed from their past and re-situated in this new, complex collection. He observes and creates spontaneous rituals, in both his paintings and his collection, that tell stories of great expectations, strained relations, and comic pretensions.

Phil Hansen, Chicago artist and a student of Yoshida, reminiscing on a typical studio critique with Yoshida, recalls one of his infamous critiques: “one of the things he was known to say was ‘could it possibly be…,’ ‘could it you see it as…,’ paying attention to the image that was emerging in the work. And he had a loud voice! Instead of asking what this means, he asking us to pay attention to what was happening while you were painting.”[26]

Walter Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking my Library,” deals with the ways in which we inherit, buy, trade, classify, and value our heritage and cultures. At the conclusion of his essay he is working past midnight going through the crates. Each book reminds him of the place where he bought it. Benjamin writes, “…the most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill…The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.”[27]

Ray Yoshida as an artist and teacher in Chicago captures the spirit of the city through his home collection, as Hansen says:

“People went around looking at garbage, looking for things that they could sell on Maxwell Street. You can go through huge quantities of things. Now there is a much more sophisticated audience. With internet, and with enough money, you could make a collection of tin toys in one weekend. The things you find aren’t site-specific, in the sense that you found something that connected to a larger moment and experience. You were open to all kinds of ‘stuff’ and you didn’t know what you were going to find that day.”[28]

A Curator’s View

Ray Yoshida’s home collection is now housed in the museum storage of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. In 2012, without explicit instructions from Yoshida’s will, the executors began the process of gifting his works and collection to various interested institutions.

Since the 1970s, the Arts Center has been involved in the preservation, study, and exhibition of artist-built environments. These artists are defined as those who transform their homes, yards, or other aspects of their personal surroundings into multifaceted works of art that, in vernacular ways, embody and express the locale—time, era, place—in which each of them lived and worked. The artists’ histories, ways of learning, and reasons for art-making are widely varied, though they share having a powerful connection to home-as-art-environment; each expresses the ineffable qualities of place according to nativist understandings and insights. Not all art environments can be retained on their original site, and JMKAC made caring for large bodies of inter-related objects from dismantled art-environments the primary thrust of its collecting efforts. In the JMKAC publication on the subject, Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists, Leslie Umberger writes, “whether a structure or a piece of land, a place identified as “home” is laden with intimate memories…artists who extensively altered and adorned their dwellings, yards, clothing, vehicles, and other facets of their immediate surroundings have a relationship to home that is simultaneously humble and proud, colloquial and extraordinary, secular and sacred.”[29] In this idea, Umberger sees sculptural forms or painted walls within a broad continuum of human creativeness and identity formation, falling in line with Prown’s definition of material culture as well as Gonzales’ term “autotopography.”

Although Yoshida’s home collection can certainly be seen as a vernacular art environment—and he as an environment builder—there are certain aspects that distinguish it from the other “builders” in JMKAC collection. Most of the artists in JMKAC’s collection are self-taught who spent years making and creating an environment from scratch, viewing their built environment as the complete vision. Yoshida, however, was formally trained and chose to enmesh himself with visual fodder meant to serve as source material for a separate art practice. Nonetheless the acquisition of the Yoshida’s collection into JMKAC’s larger collection reinforces the notion that in building his surroundings, he constructed an identity. Although his home environment retains a highly personal and imaginative attachment to the vernacular, it was built through the process of collecting and/or arranging rather than making. As such, the physical properties of the home are integral to the production, presentation, and resection of art and the relationship of art making and site are unified.

Artist-built environments are a visual record and intimate understanding of history and their place in the world. They are more than the sum of their parts, they are not merely “site specific” but are “life specific,” with clear aspects of an artist’s biography, access to material, and relationship to the surrounding community. When an art environment is relocated to a museum, these elements can offer curators interesting challenges.

The inaugural exhibition of Yoshida’s collection in 2012 at JMKAC held specific nuances and sensitivities. Rather than an attempt at re-creation of the apartment, I chose to accept and respect that a rupture has occurred, that the loss of the original context has happened. The feeling of walking into Yoshida’s apartment could not be duplicated. The question then became how to best capture and convey the essence of the artist’s environment through its components, when the original context of its place had to be left behind. That pivotal move from the site to the museum is an ongoing reality of Yoshida’s apartment and the exhibition as an opportunity to keep the story going.

Logistically however, there were a few challenges. Measurements of the apartment were not available. I opted to employ a more intuitive process of examining photos, interviewing those who had visited the spaces and honoring the relationship—rather than the precise distance—between objects. As the archives were being digitized at the Archives of American Art within the same time frame as the objects were being accessioned at JMKAC, I opted to weigh my research on the objects as primary source materials. I was able to learn through the archivist’s expertise throughout the exhibition planning, but I was not able to visit the archives at the time.

Beyond logistics, I feel that it is worth noting how much responsibility I felt to “get it right.” I had visited Yoshida’s family in Hawai‘i, met with many of Yoshida’s colleagues in Chicago, and leaned on several mentors who had known Yoshida and understood his impact. Still, many of these people hadn’t seen his collection in years, and for many it had been at least a decade since they had been to Yoshida’s apartment. I was deeply sensitive to the idea that his family and friends would see his these things in a museum, rather than his home. His passing felt recent to many people. I chose to honor Yoshida, and the way I understood him through the voices of others, by showing as much as I could conceivably fit into the space, without labels or display techniques that would favor one object over the other. In other words, I felt like I could get out of Ray Yoshida’s way and let his apartment speak for itself.

Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values was a landmark exhibition that displayed Yoshida’s home environment in an unprecedented way. With more than 2,600 objects and works of art, the contents of his Chicago apartment at 1944 Wood Street were sectioned off into nine tableaux, honoring the integral relationships among the objects and works of art as they existed in-situ. More than sixty works by Yoshida surrounded the collection and the artist’s eye. Providing further insight into the artist and his process was a looped screening of a 1990 video in which Yoshida tours the apartment and discusses his favorite aspect of the collection.

It is important to point out that the exhibition was never intended as a retrospective, nor as a survey of his oeuvre. The goal of the exhibition was to underscore the importance of the artist’s collection and to propose that it is a viable avenue to understand biography. The exhibition offered a glimpse into an artist’s way of life and the manner in which he saw the world. For many people close to Yoshida, it was also a chance to honor their uncle, their brother, their teacher, their friend.

As the Yoshida collection was being unpacked for exhibition, each object and artwork conjures a moment in Ray Yoshida’s legacy: Reassembling a wall dedicated to the works of his Imagists friends and the generations of students that came afterwards; placing the works of Joseph Yoakum above a golden handmade table built with sewing spools; marching the myriad of silent butlers along the length of the wall; carefully securing masks from around the world so as they banter with the candid words of Jesse Howard; hanging an expansive Roger Brown painting over a line-up of Adirondack tables, Lee Godie, and a game of Chinese Checkers; unwrapping pocket-sized soldiers, life-sized robots, diminutive scarecrows, race cars by the dozens, backgrounds of buttons, deliberating doll parts, masses of memory jars, buried gems, and proud artifacts. All serve as plot devices whose sole purpose is to advance the story of a teacher and artist. Placing these objects as Ray Yoshida once did at 1944 Wood Street felt important, intentional and mischievous, as I tried to thread the needle between revealing and concealing the thing-power of his home. Far more than the emotional tug of objects, ordinary “things” become museums through the innovative people who adopt them.

There is still so much to study. Now that his archives and papers are under the care of the Archives of American Art, I hope that the home collection can also be seen as primary source material for future scholars.

About the Curator

Karen Patterson is currently Curator at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. She was formerly Senior Curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC) in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Her primary focus was the Arts Center’s premier collection of folk art, self-taught art, and artist environments. She incorporated these works into curatorial projects that explore a variety of contemporary themes. She works with a range of artists, artworks, and commissioned site-specific pieces. In addition to curating the 2017 exhibition series The Road Less Traveled, her recent curatorial projects have included Ebony G. Patterson: Dead Treez, Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values, and This Must Be The Place, an exhibition series exploring the relationship between artists and their formative places. Karen completed her BA in folklore studies at Memorial University in Newfoundland, Canada, and her Masters of Art Administration at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where her focus was the home collection of Chicago artist Ray Yoshida. Prior to joining JMKAC, she developed interpretive programs for house museums and heritage sites in Canada and the U.S. and co-founded a 12-hour public art festival, Nocturne: Art at Night, in Nova Scotia.

Karen Patterson is currently Curator at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. She was formerly Senior Curator at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC) in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Her primary focus was the Arts Center’s premier collection of folk art, self-taught art, and artist environments. She incorporated these works into curatorial projects that explore a variety of contemporary themes. She works with a range of artists, artworks, and commissioned site-specific pieces. In addition to curating the 2017 exhibition series The Road Less Traveled, her recent curatorial projects have included Ebony G. Patterson: Dead Treez, Ray Yoshida’s Museum of Extraordinary Values, and This Must Be The Place, an exhibition series exploring the relationship between artists and their formative places. Karen completed her BA in folklore studies at Memorial University in Newfoundland, Canada, and her Masters of Art Administration at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where her focus was the home collection of Chicago artist Ray Yoshida. Prior to joining JMKAC, she developed interpretive programs for house museums and heritage sites in Canada and the U.S. and co-founded a 12-hour public art festival, Nocturne: Art at Night, in Nova Scotia.

Endnotes

[1] John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

[2] Ray Yoshida: A retrospective 1968-1998 (Honolulu: The Contemporary Museum, 1998) exhibition catalogue, 12.

[5] Ray Yoshida’s Adoptive Home for Misplaced Muses. A Chicago Artist’s Collection of Kitsch, Folk, and Primitive Art (Chicago: The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1985) exhibition catalogue, 1.

[6] Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” in Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1982). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc., 1-19.

[7] Gabriel Brahm and Mark Driscoll, Prosthetic Territories: Politics and Hypertechnologies (Boulder: Westview, 1995), 134.

[8] Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-network-theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[12] Lori Grove and Laura Kameldulski, Chicago’s Maxwell Street (Chicago: Arcadia, 2002), 7.

[13] John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, interview with the author, Chicago, 2011.

[22] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press), 6.

[23] The Individuality of the Inanimate Object. Movie. Directed by Seton Coggeshall, 1990.

[24] The Individuality of the Inanimate Object. Movie. Directed by Seton Coggeshall, 1990.

[25] Werner Muensterberger, Collecting: An Unruly Passion: Psychological Perspectives, Mariner Books, 1995.

[27] Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking my Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” in Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, edited and with an introduction by Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 60.

[28] Interview by author with Phil Hanson (September 2013)

[29] Leslie Umberger, “Heart of the Real” in Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists. Edited by Leslie Umberger, John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 2007, 47.

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking my Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” in Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, edited and with an introduction by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books 1969.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Brahm, Gabriel and Mark Driscoll. Prosthetic Territories: Politics and Hypertechnologies. Boulder: Westview, 1995.

Brown, Roger. Rantings and Recollections. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive.

Corbett, John and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence. Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011).

Grove, Lori and Laura Kameldulski, Chicago’s Maxwell Street. Chicago: Arcadia, 2002.

The Individuality of the Inanimate Object. Movie. Directed by Seton Coggeshall, 1990.

King, William Davies. Collections of Nothing. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Ray Yoshida’s Adoptive Home for Misplaced Muses. A Chicago Artist’s Collection of Kitsch, Folk, and Primitive Art. Chicago: The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1985, exhibition catalogue.

Ray Yoshida: A retrospective 1968-1998. Honolulu: The Contemporary Museum, 1998, exhibition catalogue.

Ibid., 10.

Ibid., 5.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

The Individuality of the Inanimate Object. Movie. Directed by Seton Coggeshall, 1990.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 5.

Interview by author with Phil Hansen (September 2013)

Interview by author with Phil Hansen (September 2013)

Interview by author with Phil Hansen (September 2013)

Interview by author with Phil Hansen (September 2013)

Ibid., 12.

Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” in Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1982). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc., 1-19.

John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, Ray Yoshida and His Spheres of Influence (Chicago: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, 2011), 3.